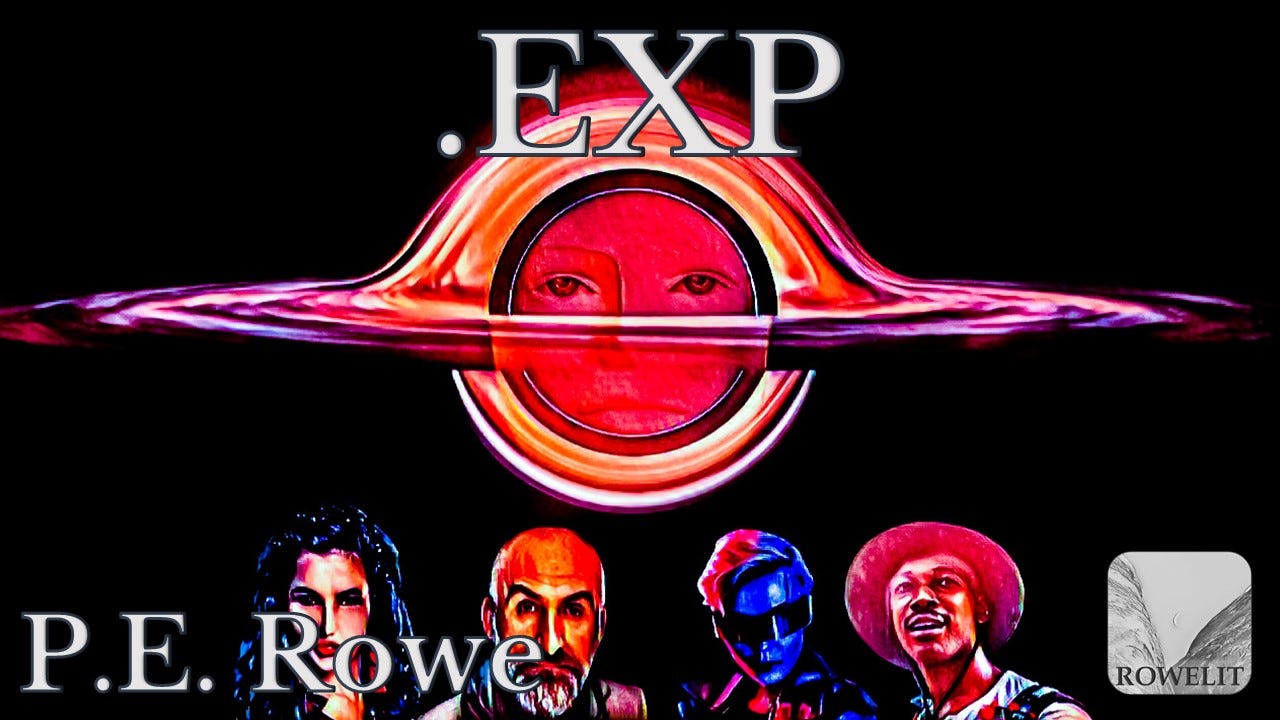

.EXP

"I am haunted by the unknown, and I know that I shall never rest until I am dead."

When all is known in the physical realm, all that remains for novelty are the different shades of nostalgia that wash over the mind in sweeping bursts of intensity and mood. Live like that for a trillion years in the darkness and the thought of starlight becomes something like a dream about a memory. They told stories about the starlight to each other, these beings who came after.

Ages before the darkness, when they first began to explore, the stars were devoid of intelligent life, and suddenly, after so much time, the universe got crowded. There were so many races and so few empty spaces. A galaxy of grand civilizations and strange outsiders. Then, ever so slowly, after tens of billions of years, they all drifted away from one another. By the time there was no light to see by, there was nothing left to see anyway. Everyone had passed over the horizon.

Gravitationally tethered in the center of a flotilla of black holes, a society of technological beings were concluding the process of a million-year plan to trigger a second big bang, deferring the heat death of the universe indefinitely. It happened that making matter was no small matter; thus, it took trillions of endling minds many ages to put such a technical plan into flawless action. The mere division of labor into manageable components had taken tens of thousands of years. Such a feat had only been possible because, since their ascendence to the stars, these endlings had shifted between a society of individual beings and a singular collective consciousness no fewer than seventy-three times. Every entity knew how to contribute to the whole.

As they were tucking their society behind the event horizon of the supermassive black hole Cloudia-K, they assigned an army of functionaries to catalog all the civilization’s imported data sets to ensure their collective knowledge survived the end of time. Once the endlings started the process, what was left behind of the old universe would be lost forever.

The transfer proceeded smoothly until the Society for Remembrance of Biologic Sentience, or SRBS as they were known, were thrown into a furor. And nothing could be more disconcerting and destabilizing to a society in transition than the collective outrage from a gathering of angry SRBS. It seemed (as no one took direct responsibility) that somehow the .EXP files had been forgotten. An uproar ensued.

When the fury of the SRBS had subsided sufficiently to deliberate on what had gone wrong, many of the obvious questions began to be asked, for instance: what was a .EXP file; why were they important; what would be lost if they weren’t somehow recovered; and could the endlings somehow reconstitute the files before it was too late? The SRBS hosted an open forum that lasted longer than the life cycles of many classes of the fast-burning stars in the universe’s third epoch. The .EXP files, they explained, were a sub-designation file derived from a technological race who had merged with their biological creators, a seemingly ridiculous and long-extinct class of higher primates called humans. They were decidedly emotional and irrational creatures, but they’d been much studied in ages past because no one could explain how such a calamity of uncontrolled emotion and haplessness could spawn artificial intelligence and somehow catapult themselves into the stars. These silly creatures had nearly extincted themselves on so many countless occasions, that by all rights, they should have died off a thousand times over before ever reaching the stars. The .EXP files had contained billions of years of digitally stored human experiences and perceptions. One of the SRBS’ planned projects during the fiery-hot years of the new universe’s birth was to catalogue the lives of these humans and other similar unaccountable creatures, whose experiences were now lost to the ages. The decision was made, after much deliberation, to reconstitute as much of the .EXP files as possible by scouring the remaining data files on the humans, much of which was in their written language, which was entirely foreign and peculiar, containing numerous concepts that were entirely alien to the endlings. So much of human experience was wrapped in uncertainty that it was impossible for such sage beings to conceive of perspectives so ignorant. The SRBS were insistent, though. Everyone must pitch in to try.

Among the endlings, there was one called Balcombe. This ambitious endling had not been sentient long enough to remember the humans directly, as a select few elders had, but had met other biological beings during the era when the stars were dying out. Balcombe, hubristically, asked for the most difficult assignment the SRBS could muster. Balcombe was given a word—curiosity—and a statement from the R.AE division chair, “We have no idea what this concept is. We need a definition that makes sense to us and a report on the experience of the phenomenon symbolized by the word curiosity.”

Balcombe, of course, had no idea what the word meant either. Because of their feeble, meat-based processor, these humans framed the entire near-infinite complexity of reality in symbolic representations of concepts—tens of thousands of them. Some were easily defined and understood, such as the color red, the neurological percept humans experienced when their eyes absorbed radiation on the EM spectrum between 625–740 nanometers. The concept of curiosity, to Balcombe and the other endlings, was impossible to process. The SRBS ridiculed Balcombe for asking follow-up questions about this assignment, for it was Balcombe who had volunteered and not their job to determine how to produce results, just to catalogue them if he did get results.

Balcombe chose the bold path of entering a controversial artificial model of extinct environments called an “ex-sim” or experiential simulation. It worked by limiting the endlings’ consciousness in specific ways that replicated the limitations of embodied biological beings. Taking away universal knowledge and understanding from an endling, even for a brief time, tended to be a disruptive and difficult process that hampered their post-simulation function. In this case, Balcombe deemed the risk worth taking, presenting the opportunity to interrogate specific humans most associated with the concept of curiosity: a scientist, a philosopher, an artist, and a traveler. Balcombe selected one of the most famous humans from each category.

Upon entering the simulation, Balcombe found the brilliance of that early universe disorienting, nearly blinding. These creatures moving through their worlds did so mostly using light within such a limited range of the spectrum that it was surprising to Balcombe how well they negotiated their environments.

The scientist, called by the mononym Shideku, lived on a world her people called Ariel-Shrieve, one of the few rocky bodies in their galaxy where humans could move about freely without any atmospheric or climactic adjustments. Not surprisingly, the people who settled Ariel-Shrieve had slowly slid backwards into subsistence lifestyles, superstitious sectarianism, and then finally, orthodox traditionalism that rejected technological advancement. Shideku was a dissident.

At first, she was unwilling to speak with Balcombe, citing busyness with the important work she was engaged in, always in secret, in VR, hidden out of the reach of the authorities, in encrypted simulations. Balcombe was tempted to respond to her rebuffs by informing her that she was not real, that her race was long extinct, and, in fact, she only existed to provide answers to the questions posed about curiosity. But given the simulation’s algorithms, that likely would have led to a long distraction followed by a reboot. If the answers had been in the code, the SRBS simply could have read the code. This was part of the experience. Balcombe played along.

At this point, Shideku was working on a seamless means of interplanetary FTL communication, one which she would perfect three human years hence, hurling both her life and the colony of Ariel-Shrieve into utter chaos. Balcombe decided against telling her any of this, instead, insinuating that future generations of scientists would benefit from her answers to these questions, the first of which was simply: what is curiosity?

She didn’t like the question. For her a question needed to be testable, preferably falsifiable in some definitive way. And this, was not her kind of science. She didn’t deny that there was a phenomenon called curiosity, because she confessed to experiencing it quite fervently. It was one of the primary forces compelling her to conduct science at great personal risk. It was mostly a feeling she got when she didn’t know why the universe worked the way it did. She asked whether Balcombe had examined the neurochemical basis for the phenomenon or had consulted first with psychologists. Now Balcombe understood why the SRBS had been so outraged. A .EXP file would have cleared up this mess instantly: simply access any .EXP with a curiosity tag and feel the feeling. Not knowing how the universe worked was a strange enough concept in itself; feeling something as a result of that ignorance was even more ridiculous sounding. Balcombe asked an even more ridiculous question: what does the feeling feel like?

“For me,” Shideku said, “the feeling that is most closely related is desire…or perhaps compulsion. Wondering about something is almost a type of mental illness for me. I cannot put my mind at rest until I fill that gap in my knowledge, yet I know that the second I fill that hole, I will be driven by the new holes uncovered in opening up the first inquiry. It is like an insatiable hunger of the mind. All of this is undergirded by a sense of awe for the complexity and beauty of the universe. I am haunted by the unknown, and I know that I shall never rest until I am dead.”

“Sounds most uncomfortable,” Balcombe said.

“It’s actually quite beautiful in the abstract,” Shideku said. “Late at night in the lab, unable to turn off my mind and put my work away, knowing that my relationships will suffer, I will go hungry and be frustrated and exhausted, all to test a theory that may never reveal itself in any fruitful way, yes, that is when it’s unpleasant. But I don’t know how to be any other way.”

“That is an unfathomable state of being,” Balcombe said.

“I cannot fathom your being,” Shideku responded. “If you know everything about the physical universe, what’s the point without any mystery in your existence?”

“Chance is a part of every equation,” Balcombe said. “How chance manifests is the mystery in our being, hence my presence here. No one could have predicted the missing .EXP files and the chaos that has ensued. I thank you for your time. Also, know that your pursuits shall bear fruit one day, Shideku.”

Balcombe decided that even though scientific records of human neurology could help to define curiosity, science could only yield a description of what curiosity was, not the experience itself, which was what was lost in the misplaced files. Balcombe was eager to speak to another luminary who might be able to help uncover the mystery of the feeling Shideku had described. The next human on the list lived on Haal, an interstellar vessel on a two-hundred-year voyage from Idrion into uncharted territory in the inner Scutum-Centaurus, a fifth-generation exodus ship. The passenger Balcombe had come to question was Ivon Arryon, best known for his philosophical tome on the value of being human and frail. Arryon’s most enduring theory posited that humans’ greatest value stemmed from their limitations—that in contrast to AIs, who could access any information on command, humans experienced ignorance and, therefore, acted upon the universe in surprising and unpredictable ways no algorithm could ever replicate. They could also never not be this way—human biology compelled it. Humans would always be religious thinkers, compelled to act on biologically driven schedules in the absence of full knowledge. That compulsion drove value propositions, morality, communitarian desires, family formation, sensations like love, courage, the veneration of beauty. Arryon, in his whole life, never once stepped foot off the Haal, as he was born mid-transit. Yet he influenced the behavior and thinking of trillions of humans who followed. Yet another manifestation of the mystery Shideku had referenced.

Arryon greeted Balcombe with great joy, especially since this stranger brought with him a philosophical matter he’d never pondered. This visitor’s perspective stood in stark relief to his human experience, and it seemed to confirm Arryon’s position. Here was a visitor so learned that the only substantive question left to be answered was what it felt like to have questions.

“That sounds awful,” the philosopher stated. “I’m not sure what I would do if I had all the answers.”

“Is that not why you pursue your vocation?” Balcombe asked. “Why would you dedicate your life to asking questions if you had no desire to answer them?”

“Would I not then cease to have a purpose?”

“What is the purpose of any human?” Balcombe asked.

“Or technological form, for that matter?”

“I’ve noticed that you seem to speak in the form of questions, Mr. Arryon. Yet when you write, you make large claims and untestable assertions. Is this what it means to be a philosopher?”

“Is that your understanding of what I do?”

“To be fair,” Balcombe said. “I don’t understand what you do, which is why I’m here with you. And, it seems that, yes, you have answered three straight questions with questions. That constitutes a pattern.”

“But you stated that you wished to know what it was like to experience curiosity. Why then do you suppose I might ask you these questions?”

“You seem to be attempting to simulate the experience by prompting me with questions, Mr. Arryon. However, if I were truly curious, would it not be I who was generating the questions?”

“Exactly, Balcombe! Well done. Do you not feel the desire to have those questions answered?”

“Desire, no. I would say need, for the sake of the SRBS and my own standing among my kind.”

“But you do prefer to have the question answered?”

“That is preferred, yes. But I would ask you, philosopher, because I am uncertain of something you said earlier, you ask questions but do not seem to desire the answers, at least not definitively. Is that curiosity?”

“It’s not that I don’t want the answers, more that I relish the shifting seas of the mind as I deliberate the possible approaches to answering the question. A definitive answer to every question would leave me very little joy. I feel curiosity, certainly, but it is more for the pursuit of the answer than the answer itself. Is that clearer? Does that help you in your pursuit, Balcombe?”

“Sadly, no, Ivon Arryon. I still have no meaningful answer that satisfies. Perhaps a great artist will be better able to provide a fruitful avenue for explanation.”

The artist, Amarangia Mora came from an era of revival, on Earth, several thousand years after the first return. There was glorious infrastructure written about in the archives, some even with original documentation from the historical record. Amarangia, like most artists of that era, worked in digital spaces where she was not limited by the problems posed by physics, logistics, or weather. However, desperate calls kept going out for artists in the recreation of the old world in the old ways. Cathedrals, fora, fountains, paintings, sculptures—it was important to the people in that time that the items adorning their new cities, ancient as they looked, should be hewn, erected, formed, and adorned by human hands, and no human hands, perhaps, were ever as deft at putting the illusion of life into lifeless objects as the hands of Amarangia Mora.

Much of what she painted was recreated from images in the archives; however, Amarangia gained her fame by insisting on an equal division of her time and workspace. She would dedicate half of her work to restoration. The other half, she demanded, was for the creative spirit she claimed had to be allowed to thrive within or its absence would kill her love of art. And she worked in public; under the scrutiny of peers and ignorant bystanders alike, Amarangia would paint, resurrecting lost masterpieces as the onlookers marveled at her genius. Then turning to a blank wall, she would create original masterpieces that no hand of the future could hope to match.

Engaged in such work was the prodigious master when Balcombe came calling, hoping an artist had something useful to say about curiosity.

“For me, it hides in the darkness between pieces. An image can speak without ever having spoken to me.”

“What does this image say?” Balcombe asked, pointing to the magnificent portrait she had nearly completed in the apse of Theodorus’s Vault in Cargyll, less than fifteen minutes upriver from the spot where the city of Rome once stood. The image was of Ceres, wreathed in golden ivy, raising the harvest in the wide-ranging fields of the surrounding countryside.

“It’s more a feeling than a statement. I can’t say exactly in words.”

“How does it speak then if not in words?”

“As I said, in feelings, and those feelings manifest as images that are not quite fully formed. It’s as though there’s something meaningful just outside the reach of the fingertips.”

“How do you know what to paint if the image is not formed?” Balcombe asked.

“If I understood what I was making, what it spoke into the world, then I would just be a painter, not an artist. Art isn’t made in the mind of the artist but in the hearts of the people it touches. The artist can no more know its meaning than she can know the mind of another. She can only guess based on experience and shared culture.”

“Then where does curiosity lie in the process?”

“Art asks questions, but more importantly, it manifests in ways the artist can’t explain. Where do these ideas come from? How do I know how the goddess carries her hand? How do I know exactly what time of day it is that the light hits her just so?”

“How?” Balcombe asked as though the questions were not rhetorical.

“How indeed?” Amarangia said. “It’s something of a miracle that works through me. A trillion tiny neurons fire and chart a course through my mind, away from darkness, toward beauty, and somewhere in that process you’ll find the wisdom of the universe.”

“Somehow, dear artist, even though you paint with oils on a physical surface governed by porosity, humidity, temperature, shape, viscosity—all physical forces—you have managed to give an answer more cryptic than the philosopher, a true achievement in ambiguity.”

“That is because you mistake me, Balcombe,” Amarangia said. “I don’t work in the physical. All those things you named are just the medium, the message lives in the metaphysical. I work in meaning.”

What meaning, Balcombe couldn’t tell, nor did any meaningful sense of what curiosity was arise during this conversation with the artist. And with each passing encounter, Balcombe grew more determined to answer the question, desiring nothing more than to possess some meaningful understanding of the concept, much like the way Shideku had described science, nearly a compulsion, a feeling that arose quite independently of Balcombe’s consciousness.

There was yet one more name on the list, Oswin Rudinelsa, the traveler. His fame grew upon calculating as a teenager, during a famous flight of curiosity, that despite it’s nearly unfathomable circumference—at least by human standards—that if he walked between eight and ten hours a day, it would take him just under forty years to circumambulate the planetary ring of Athos, a feat that had never been attempted, and one that had not been equaled since Oswin Rudinelsa completed the nearly impossible undertaking, minutes before sundown on his sixty-fifth birthday in the city of Ithaca. His fame waxed and waned as people on the ring took interest, lost interest, and took and lost interest again and again over the course of Oswin’s lifetime. Some fellow wanderers took years off to walk with Oswin, forming deep friendships over pieces of his journey, his life. Many of these companions would be there to greet him in Inmann Square when he finally arrived. More than a few were long since dead. Oswin came to embody the concept of curiosity for the Athosians. His obituary declared that he was possessed by an unwaning spirit of adventure and a desire, not just to see the extent of the ring in a way no other human had, but even more, a desire to meet the people he shared space with as they spun around the gas giant Athos together. He estimated that he’d touched hands with at least fifteen million people who’d descended upon his route to cheer him on as he passed.

Balcombe found Oswin Rudinelsa nearly fifty kilometers outside of Sabre City, roughly a third of the way into his epic journey. He was, at that moment, passing, quite anonymously, through a shady causeway under a verdant archway of tall sugar maples. Balcombe, taking human form, ambled up beside him and began to ask the famous traveler about curiosity. Oswin was happy to talk.

“I didn’t really think about curiosity when I first started walking. For me it was the idea of a monumental challenge that had never been accomplished before. But that challenge was so big, I found I couldn’t think about it or I would fixate on how something so big couldn’t be done. I learned very fast that I didn’t need to get around the ring. I needed to get to the next town, and to do that, I couldn’t even think about tomorrow or even a point I could hardly see on the horizon. I had to get to the next building, the next square, the next tree that lined the roadway. And to do that, I learned that I had to savor the difference in everything. Many people say the ring is too similar. Every city looks the same. This is not the case. Definitely not the case.”

“Our kind cannot help but see the similarity in everything,” Balcombe said. “We explored every system in the galaxy in intricate detail. What we found was that there were a limited number of elements and, though there were certainly outliers, these elements had ways in which they commonly combined. Each star was unique in one hundred billion, yes, but there was far more similarity than difference. It was the same with life forms—certain structures that tended to support life more readily proliferated, those that didn’t fell out of existence. Once we’d examined so much of the galaxy, we’d seen enough to know what we would find elsewhere and could even predict it with great accuracy. The same combinations of elements, adaptations, technologies, over and over, again and again. That is the nature of the universe.”

“We could be no more different, Balcombe, my friend,” Oswin said, looking over at this peculiar visitor, still not breaking stride. “It’s true that in over a decade walking I’ve seen many similarities in the structure of the ring, the architecture, the trees, the food, the people. But I have had a lot of time to think on this journey. Several years ago, I did ponder this problem as the similarities began to trouble me. I would think, is this all there is? But I kept walking and thinking about it. And I thought, what would this journey be if I came through again a year later? Could this ever be repeated?

“It occurred to me that the city I was passing through wouldn’t be the same city. The children who had come to shake my hand would be taller, smarter, more responsible. Some of the old folks would have passed, leaving their children and grandchildren behind. Restaurants may have closed; new ones opened. Every time the sun rises on a city, it rises on a new city. The differences might not be perceptible to the residents, but they know it. They feel it. That’s the challenge of life, negotiating that new, unknown place. If people enjoy life, Balcombe, that is what they enjoy about it, negotiating the unknown, observing, relishing the uniqueness of moments that have never come before and will never come again.”

“I suppose in that way then, it would seem curiosity is built into the human condition—the desire to know the world around you and explore it.”

“Yes, I think. Even if we humans lived for a million years and we saw all there was to see, tomorrow would still be another day. Every day we could wonder, who will I meet today? What will I see? What will happen? That won’t change, so long as we remain human.”

“I think I understand your meaning,” Balcombe said. “But I am still no closer to understanding how to categorize the experience for my superiors. I continue to seek answers from those most capable of providing them, but unfortunately, I have yet to find a definitive experience.”

Oswin Rudinelsa smiled and adjusted his hat, looking over toward Balcombe. “I bet if you keep searching and searching, someday suddenly it will hit you. Curiosity has been with you all along.”

“Sadly, not in our kind,” Balcombe said. “Nevertheless, thank you and goodbye, Mr. Rudinelsa.”

When Balcombe returned from the simulation to Cloudia-K, the endlings’ black-hole hideaway, the SRBS were eagerly awaiting a report. Balcombe reported accurately on the perspectives of the humans who most exemplified curiosity as a characteristic. All the technological beings invested in the reclamation project paid careful attention to the report, for it was a key concept, not just for the human catalogue, but for biological beings writ large. Embodiment, as the project was discovering, had come with constraints the endlings could not understand, and these constraints gave rise to instincts that had compelled these biological creatures to explore, discover, and create.

Balcombe concluded the report by stating: “I truly desire an answer to this most perplexing question and would be willing to continue this pursuit indefinitely if I had any inkling curiosity’s meaning would reveal itself. Unfortunately, I have no answer to report, and I am convinced that, given the nature of our being, curiosity may be beyond us.”

Balcombe’s closing statement sent the gathering into an uproar, but quite unlike the attitude before. The large collection of endlings did not seem troubled by Balcombe’s failure at all. There was a noticeable change in demeanor among the SRBS when the chair of the committee on the recovery of abstractions and emotions directed Balcombe to confer with Krichaps, a similarly ambitious endling who had been assigned to recover the concept of irony. Krichaps was kind enough to put Balcombe’s confusion to rest by communicating that Balcombe could now access the generalized file tag: human/baseline-emotion/curiosity.exp. And as Balcombe absorbed the new information flow—including the news on both how the files had been misplaced under a subheading in “lost empires” and how a minor functionary had inadvertently recovered them—Balcombe now understood. There was now a feeling to go with the realization that the search for curiosity could have begun and ended with Balcombe’s own paradoxical desire to find the very desire that had prompted the search in the first place.

This, Balcombe decided, was something new and unpredictable. Chance, it turned out, even at the end of the universe, still had a curious way about it.