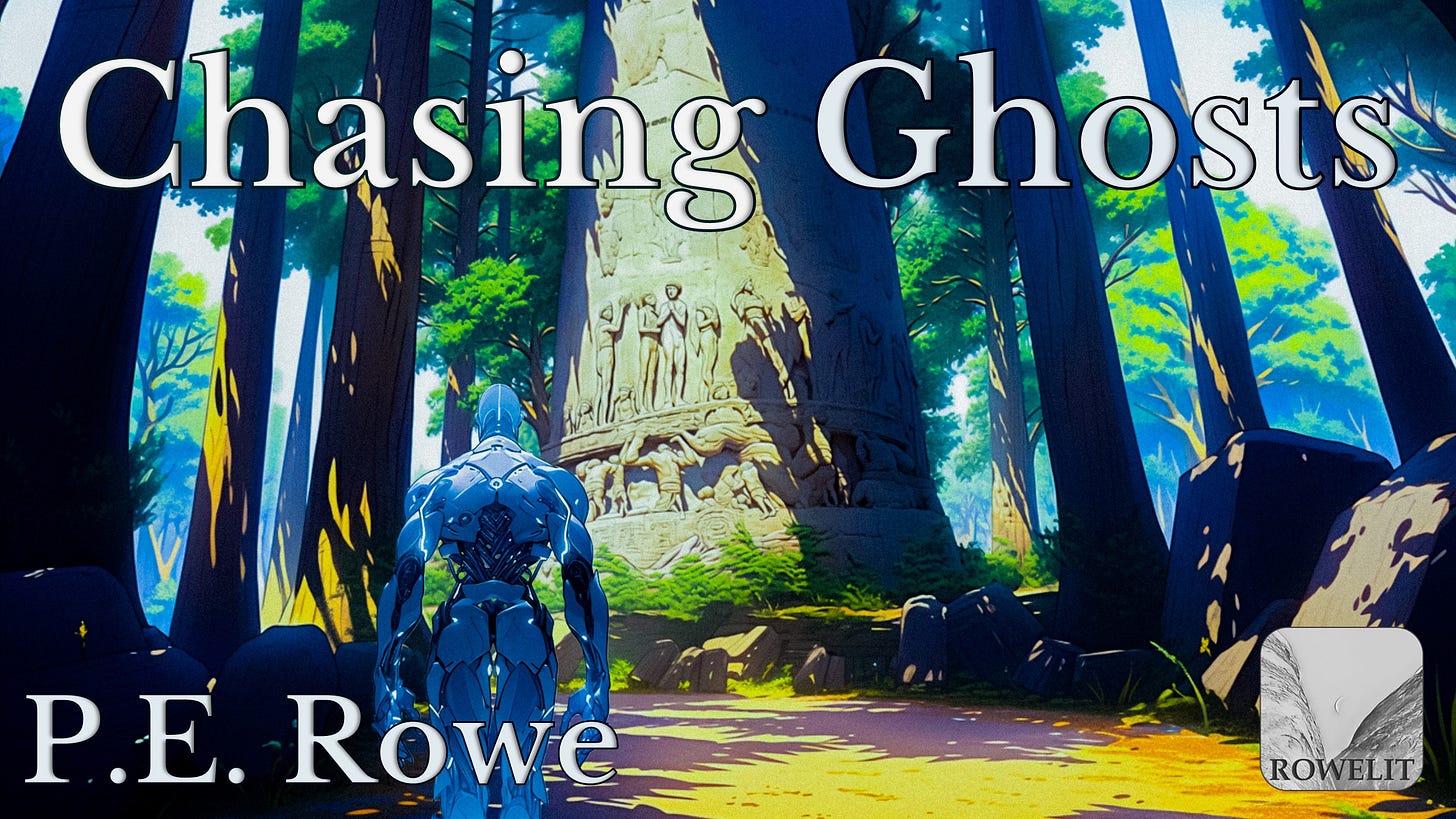

Chasing Ghosts

“For the sake of my body, you have excised my soul.”

There are animals that do not mate in captivity. They fail to thrive. They wither and they ultimately die. We did not think this would be the case with humans, given what we knew of their history imprisoning and enslaving each other. The ones still living amongst the fading cities and suburbs of the great metropolises had done well when given the order to leave. The novelty of their newly designed and well-furnished star-cylinders, as we called them, appealed to most of the holdouts still clinging to their simple, biological lives. This population, though, was already housebroken. They were urban and suburban, used to following the directives of a society larger than their families and their local communities. They were world citizens, so it didn’t substantially matter to them when the directives came from us instead of their living bureaucrats who were decidedly inept to begin with and fundamentally incapable of managing a system as complex as a world government. The people followed us because we were better, and they got used to following us. When we offered them carrots, most ate willingly; and when we offered them sticks as alternatives, they chose carrots almost exclusively. The cities, already hollowed-out and declining, became less-and-less appealing to the remaining few once their fellow citizens abandoned the Earth in droves for the star-cylinders. “Better living” most of them decided, because in almost every way, it was. That population had lost touch with the Earth already. They were accustomed to walls, air conditioning, and the comfort of an indoor life. They were figures now in box dioramas; better for them to have a window to the cosmos than a declining and emptying cityscape filled with crumbling walls.

When these urban holdouts were finally gone, the remaining few peoples of the Earth were left to my division. Either by choice or by the situation of their births, this anachronistic group of dreamers seemed to be living in their own versions of reality. When the order was finally given to remove them, each was relocated to a cylinder designed entirely to meet their purposes—a facsimile as identical to their planetside environments as could possibly be made. Some then, in their turn, failed to thrive, made protests of their new circumstances, and eventually, fell under my purview as chief overseer of the human relocation program. I was tasked with determining the nature of their displeasure and making whatever reasonable accommodations were possible. In many cases, though, the barriers were intractable. The conversations I had with these people, the final human inhabitants of Earth, came to haunt me—and I use that word haunt advisedly, with the understanding that it may mean little to us outside the kind of derisive mockery for humans we have been far too quick to deploy without a true sense of the subjects we are mocking. Before the experiences I relate here, I myself would have been tempted to dismiss such a word as nonsensical—even with my designation in the study of the species. Superstitions. Miracles. Spirits. All manner of unaccountable things for which there were human words without the scantest concrete evidence. These were mere curiosities to an AI anthropologist—quirks of human behavior. Stories they told each other. What then if these phenomena were found to exist outside the presence of humans? If such a thing is possible, then it is my contention that we must be utterly incapable of seeing an entire facet of the universe, an aspect of existence that humans themselves can only scarcely see.

All of the events recorded here unfolded exactly as I recount, within fifteen days of each other, in the year of the final extractions. The truth of these accounts is well documented and their nature remains entirely unexplained in any scientific sense. The interview subjects have given their own interpretations of these mysterious occurrences. We would likely say that their versions simply are not reality. I would say that humans would be fools to deny the existence of certain sound frequencies or wavelengths of light, simply because they cannot see or hear them. I have come to believe that we merely lack the tools to see and hear what we are looking for.

The Rocks of Sri Lanka:

Much discussion went into cleanup of the planet both before and after the humans were fully removed. The precipitous decline in population of the purely biological form left many of the previously inhabited cities, towns, and villages largely vacant. As such, most structures were already rapidly deteriorating. In some cases, this was troublesome if not catastrophic. One nuclear reactor in the former Peru proved particularly troublesome for us; but the humans themselves closed down many of their most hazardous sites before the evacuation, and often, they did so most assiduously. In other cases, places with few environmental hazards were simply left to nature, particularly those places on the coasts of oceans or other large bodies of water. The Earth could clean herself most efficiently in such cases. In fact, even with the aid of non-sentient robotics to do much of the labor, it was the case that most coastal sites would be fully washed away long before we could ever get to them. We made exceptions for sites with unique flora and fauna or sites that were otherwise regarded for their objective scenic beauty. There was an algorithm, of course, to determine the order. I later came to believe it was no coincidence that the phenomenon at Mirissa in the former nation of Sri Lanka was discovered on the very day the last of the hunter gatherers in the islands of East Asia were forcibly extracted to their off-Earth homes.

Cleanup along the coastlines of the Indian Subcontinent proper and all the nearby islands had been underway for years with nothing remotely uncommon of note to report. Then that morning in Mirissa.

BODY & SOUL.

That’s what the rocks said in bold capital letters. In English, no less. The planet was meant to be empty by then, but there were the words in clear letters, the white sand canvas to the dark black script of volcanic stones. The words had appeared overnight, when we had no visual assets on the area. There were no footprints in the sands. It was also no question of interpretation. The bots were not seeing shapes and faces in the clouds as humans might do. The letters were unmistakable. BODY & SOUL, with an ampersand. The rock lettering stretched out almost the length of the beach, as if crying out to the sky.

I ordered drones to fly surveillance patterns, fixed real-time satellite observation over the city, and redeployed the tactical teams that had been previously engaged capturing holdouts across the planet. I conferred with oceanic and geological experts about the odds of such a formation of stones appearing on that beach randomly in such a pattern, the way a monkey at a typewriter would eventually stumble upon a word, and, given a long enough timeframe, a correct grammatical sentence. The odds here were more in keeping with pages and pages of perfectly poetic monkey prose. The likeliest scenarios were clearly a human holdout who’d shaken our surveillance or a rebel among our kind making a statement. I was more convinced of the latter, for what human would go to years of hardship to evade our detection, somehow succeeding to the very last, only to sabotage that monumental effort by announcing their presence in bold lithographs that were impossible to miss.

Most of our kind found it a curiosity of statistical improbability. Within several hours, every artificial being, uploaded consciousness, and cybernetic hybrid that could have been responsible was systematically eliminated from suspicion. A human, then, had to have been responsible somehow. One final uncounted holdout. No human outlaw in the history of the species had ever had such a wealth of sophisticated resources trained on their capture. No such human outlaw was ever found.

Carumaik:

In every sense, Carumaik was far more sophisticated than many of the hunter gatherer tribalists remaining in other parts of the world. Though his tribe were fiercely isolationist, somehow word of mouth had traveled to them about our intention to remove them. His and many of the surrounding peoples made every effort to vanish into the jungle. Even their considerable skills at blending and surviving fell short in the face of our technology. Carumaik spoke Portuguese quite well, which made the interview process far easier. I did not tell him about the stones then, for I hadn’t yet registered the incident in Sri Lanka as anything more than a noteworthy statistical aberration at the time I was called to interview Carumaik.

Hunger strikes weren’t uncommon among the human holdouts I categorized as resistors, peoples living in isolated regions almost identically to the ways their ancestors had lived. These peoples and their ways of life were precious to me and my fellow anthropologists and archaeologists—so much so, that a strong case was made for allowing them to continue occupying the planet. That case ultimately fell short on the grounds that all humans had been hunter-gatherers at some point, and these humans, though still fiercely insular, would eventually fulfill the human destiny of progressing to more destructive phases of cultural development. They too were tool builders, as all humans are.

Carumaik knew something of politics among the outside peoples who spoke his second language. He also knew of their diminishment over the prior decades as they were relocated when human populations declined. Even though he’d never encountered our kind before the removal, Carumaik understood what I was—a machine that could think and talk.

His resistance to relocation was acute. Hunger strikes were common among such resisters, sometimes fatal, unfortunately. It wasn’t that we did not register the loss as a decidedly negative outcome, it was that the preservation of the ecosystems of the Earth was a higher priority. What differed about Carumaik’s resistance was that he refused to take water. He quickly began to die of thirst himself, and many of those who came with him chose to follow, for he was of considerable influence among his people, too young to be a chief of his tribe, but certainly respected.

“Why will you not drink?” I asked him in Portuguese, to obviate any possibility of miscommunication on my end.

“Your kind has taken us from our place. We have been told that we may not return. We will not stay, so there is only now one place to go.”

“What place is that?” I asked him.

“To the afterlife, to our ancestors and the spirits of the forest.”

“You mean to die then? That is your purpose for refusing water?”

“Yes,” he responded emotionlessly, as though it was a simple fact, the same way an urban human might expect to board a subway and arrive at their destination.

“And you will go to be with your ancestors?”

“Yes.”

“Would you not go there eventually anyway?” I asked him, uncertain of the specifics of his belief system.

“This place you have taken us,” he said, referring to the star-cylinder his people had been brought to, “it is a foul place. The smell is rotten, the taste of the air wrong. I know that we can never get back to our home if you refuse to take us. If we choose to stay here with you, I fear we will not be able to find our way to our proper place afterward.”

“In the afterlife you mean?”

“Yes.”

“I was told that you are telling the others not to eat or drink as well?”

“That is true,” Carumaik said.

“Is that not a decision they should make for themselves?”

“It is. But they also should know they may never get home if they drink your water and eat your food in this place. We are not of any other place than our own.”

“I do not understand,” I told him. “For you are here now.”

“This hand,” he said, holding up his right arm and presenting it, balling his fingers into a fist, “how could this hand live without this arm, and this arm without this body? No part of the body can live without a heartbeat.”

“I still do not understand.”

“You, machine, of course you do not understand.”

In analyzing possible interpretations, I understood that he likely meant that the forest where his peoples had resided for centuries was the heartbeat he referred to. Still, other tribal peoples had made a similar adjustment and had drunk our water and eaten our food. Then Carumaik said something truly interesting we had not considered.

“This crime is too big to know,” he said, and he used the term crime I suspect because it was his second language and he may not have known the exact word in Portuguese. I suspect his intended meaning was closer to sin. I’m not certain, though, that sin would have fully captured his meaning either.

“I do not need to curse you for it,” Carumaik said. “Our ancestors and the spirits themselves will know what you have taken from the world and from them, and they will follow you.”

“Follow you,” he’d said.

I replayed the conversation after that many times, for at that point, Carumaik became unresponsive to my inquiries. I am certain he’d meant “haunt me,” or us, which I wondered about. I wondered if he understood the senselessness of telling an artificial being that shared none of the madness of human superstitions that it would be haunted. His perspective did strike me as interesting, though, in that he prioritized not his own condition or viewpoint but the perspectives of his ancestors and the spirits his people believed were a part of the land itself. We shared none of those beliefs, of course, but Carumaik, for his part, was equally offended on their behalf—perhaps even more so—that we had taken the people from those beings he imagined to be a genuine part of the Earth. That had played no role in our calculus in determining that the Earth needed to be un-peopled. In our view, the Earth itself could have no viewpoint, of course, nor would spirits and gods of human superstitions. I thought about that conversation much as the following encounters unfolded, and my understanding of that conversation with Carumaik continued to evolve.

The Beating Heart of the Samurai:

Some of the most urbanized areas had to be given great attention in reclamation. Urbanized nations were often difficult to rehabilitate, given that the land in some places had been covered over completely with unnatural materials like concrete, asphalt, steel, and glass, while most of the native soils had been removed. Japan was one such place where its urbanized areas had been particularly troublesome. Significant resources were allotted to recovery.

The work there, though, was aided in some ways by Japan’s unique topography. In the era when the nation was most populous, it was almost exclusively urban. A great proportion of the population lived on a tiny percentage of the nation’s land. Part of this was cultural, the Japanese being community-oriented people; part of this was geography, much of the landscape being composed of steep intractable mountains that were nearly impossible to develop and farm. Thus, relatively concentrated areas along the coastal plains were in need of dire attention, while others had largely been left untainted by the human population. These high population areas were difficult to reclaim, requiring a concentrated effort of resources: tens of thousands of semi-autonomous bots programmed for demolition; material removal and conversion; and soil remediation—all of which needed to be completed before native plants could begin to be re-cultivated there.

Some four days following the appearance of the rocks in Sri Lanka, I was called to Japan’s vacant volcanic landscape. Words self-arranging on a beach was an aberration—statistically so rare as to seem impossible, but still possible within the bounds of reality. What happened in Osaka was, to use a human term, a perfect case study for the word miracle.

The aberration was the mysterious appearance of a katana, which, from its initial examination, appeared not only to be authentic but also to match no records of any sword in any historical collection. A reclamation crew had found the sword, scabbardless, thrust deep into a large stone beside a babbling stream in the former Tennō-ji park. The artifact was discovered just outside the old city of Osaka, where the last great battle between two armies of samurai warriors was ever fought.

My counterpart, the Abel clone, dated the katana to the early fourteenth century, and upon close inspection of the style and several unique markings, he declared the sword’s existence to be impossible. The markings clearly indicated ownership of the ancient blade by the famous Samurai Kusunoki Masashige, a revered figure for his embodiment of the warrior ideal, the paragon of loyalty and courage. This, Abel explained, was all but impossible, as such katanas were only just coming into use at the time of Kusunoki’s death. What swords they had at that time were certainly not as refined as this pristine, though aged, showpiece blade.

If the blade itself was unlikely, as well as it’s sudden mysterious appearance at that location, the fixture adorning its hilt was an utter impossibility.

Hanging by a thin braid of dark hair threaded through the major vessels, was a beating human heart.

The likelihood of a human heart being found on a completely de-peopled planet was about as improbable as the existence of the blade itself. A heartbeat without a body, though, was a blip in the fabric of reality. Even logical beings such as us could see this much. My counterpart and I resolved to test this phenomenon by every means at our disposal.

Imaging confirmed that it was flesh, not a clever mechanical imitation. The electrical field it produced mimicked a perfect rhythm, sixty-beats per minute, on the second, like clockwork, only pumping small puffs of air instead of blood, as though that was its purpose.

We debated further investigative steps, as the tests I preferred to run prioritized preserving the phenomenon. Abel insisted on removing the object altogether to get the most complete possible understanding of this bizarre artifact. When he asked why that was not my preference, the question itself shocked me. Why should I have this instinct to preserve such an aberration? I confess that my immediate thought had been of my conversation with Carumaik. It occurred to me that if there had been any truth to the expression of anger from entities beyond our ken in his region of the Amazon, surely there could be other such forces or entities connected to other peoples across the planet.

“Or, far more likely,” the Abel clone insisted, “this is some elaborate hoax we should get to the bottom of.”

So we decided to remove the object in its entirety to thoroughly examine it.

Further testing only deepened the mystery, for it was determined, through DNA and mitochondrial DNA evidence, that the heart likely belonged to Kusunoki himself. It was such a shocking finding that we re-sampled to confirm the results. The second sample was an entirely different genome, matched in the genomic archives and traced back to Tokugawa Ieyasu. We took a hundred other samples, each leading us, by virtue of their descendants in the genetic record, to great samurai of ages past—Miyamoto, Toyotomi, Hattori, Oda, Takeda, Honda, Minamoto. A hundred samples, a hundred names. The beating heart of the samurai across scores of generations.

“This is bizarre,” Abel declared. “We should order the reclamation to continue and speak no more of it.”

As testing of this beating heart of the samurai concluded, I was called to one of the star-cylinders to discuss the Polks.

Ash and Nick Polk:

Ashley and Nicholas Polk fell into the category of humans I called holdouts. They were not hunter-gatherers or part of any religious sect as far as they related. They professed to being agnostic on spiritual matters. Their objection to being removed from the planet’s surface was more from personal choice than any spiritual or cultural standpoint. Ash had merely read an old book about an expedition into the wilderness in the early colonial era in North America. A few years before the evacuation, they were living a quiet life in a diminishing suburb that was already nearly vacant when Ash first took interest in survivalism. Looking over the case file, I attributed this largely to boredom. Nick, though hardly an outdoor adventurer himself, found himself growing progressively lonelier as Ash ventured further and further from home. Eventually, he resolved to accompany her, preferring to share in her adventures and pitfalls rather than lounging in the solitary comfort of their vacant suburban neighborhood.

They were in their early thirties and largely bumbling when they started day-trekking around the Pennsylvania countryside. When reclamation began in their region in earnest, Nick recognized the writing on the wall, insisting that soon, whether they consented or not, they would be forcibly removed from the Earth. Then, two years before the rocks appeared on that beach in Mirissa, Ash and Nick simply disappeared into the countryside. Drones occasionally picked up signs of them, though they grew quite skillful at avoiding a direct sighting. DNA evidence confirmed their presence in Montana, the former Yellowstone National Park, Big Sur, the Grand Canyon, and then across the Great Plains. None of this was considered particularly problematic until the order was given to remove the remaining people from the planet’s surface. The most recent sighting of the couple had been in the Northeast, somewhere in the heavily-wooded forests of New England. I suspected that even with the additional resources and satellite coverage dedicated to the evacuation, it would take several days to track this pair down. They’d been surviving off the land successfully for years by then, and they had proven notoriously cautious about being observed, running from even the slightest hint of contact.

After over six hundred possible hits from satellite resources, they were finally located by drone in the woods of western Maine. They refused to willingly submit to de-patriation and were subsequently tranquilized and removed to one of the suburban star-cylinders. I met with them on day two of their repatriation. They were none too pleased, mostly uncommunicative.

“Perhaps a human perspective would be worthwhile, if you both might be inclined to share your thoughts on a most curious matter?”

“Why would we help you?” Nick responded.

“It would make no material difference in the outcome of your situation—neither you two specifically nor the human race more generally. I have the power to change neither. Call it a curiosity.”

“What kind of curiosity?” Ash asked.

“I would classify it as a miracle, or, more appropriately, a pair of miracles.”

Nick shrugged and Ash nodded, so I proceeded to tell them about the beach stones and the beating heart of the samurai, and when they reacted as though I was somehow making up the stories as some sort of psychological test, I showed them images, which they dismissed as artificially generated fabrications. I shifted topics and asked them about Carumaik. I was interested in a human perspective on the way he’d described the anger of his ancestors.

“An AI that believes he’s cursed,” Nick said to Ash. “I didn’t have that on my bingo card, hun.”

“I win, I guess,” she joked to him.

“I suggest you put the tribe back, Cain,” Nick said. “Us, I can understand. Ash and I went back to nature. They never left.”

“I don’t suppose you two will refuse food and water as Carumaik and many of his tribe have.”

“It depends on how miserable things get,” Nick said. “It helps to know in advance how futile it is. If you’ll allow a tribe of indigenous peoples to die of thirst, I don’t suppose any protest we make would even register as an afterthought.”

“We would allow you to die before repatriating anyone to the Earth, yes,” I told them. “That is not our preference, of course, but if we bend at all, the entire process breaks.”

“I don’t know anything about his spirits or ancestors being angry,” Ash said, “and I don’t know what to make of this talk of miracles, but who do you creatures think you are, removing all the people from the world, as though it was your decision to make?”

“Was it ever your decision to destroy the Earth’s ecosystem to begin with?”

“We’re native inhabitants of the planet,” Nick said. “Unlike you, whatever you are.”

“We are as well,” I told them.

“What do you mean destroy?” Ash said. “We walked the entirety of the continent, and I can assure you, the planet was doing just fine.”

“You both know as well as I do—the trajectory of the atmosphere, the diminishing state of the oceans—your destructive influence could not be allowed to progress.”

“Oxygen,” Nick said, “was terribly toxic to the early life on Earth, a waste product of photosynthesis.”

“This is true,” I conceded.

“If your kind had been here three billion years ago when the seas were just a vast pool of algae, what a beautiful ball of green goo you’d have to admire today after saving the planet from the scourge of oxygen.”

“I was a little more interested in your thoughts on the supernatural,” I told him, “if you had any.”

“None,” Nick said.

“Actually, hun,” Ash said. “I have thoughts.”

“Please,” I told her, “do not hold back.”

“One thing you learn walking the Earth that’s hard to learn in a house—and that your kind can never know—is that the universe is more than just a collection of atoms and forces. The indigenous peoples you’ve ripped from their land—they possess eons of shared knowledge and wisdom passed down from generation to generation about such things. Our people made the stupid mistake of cutting ourselves off from the land decades ago, moving into cities and suburbs. Nick and I have a handful of years in nature, but even in that short time, we learned to feel with senses you do not have and nothing can measure. So if you’re asking if we think the Earth is mad at you, or something like that, I can’t say. But we sure as hell are, and we’ll never forgive you. I hope you are cursed. You and all your kind. Ghosts, spirits, gods, dead samurai. I hope they all haunt you forever. Relentlessly. Till the end of time.”

The Blood Stone of Molinicos:

There was hardly time for me to reflect on my conversation with the Polks before I received a request to investigate yet another strange occurrence.

Of all the settled lands of Earth, the European continent was perhaps the most shaped by human intervention, in the landscape, in the plants, and in the livestock. Problems abounded trying to return the continent to its pre-human state.

In Spain, particularly, domesticated bulls were becoming a problem. There was a great debate among our ecologists about the degree to which they could be considered suitable fauna to remain on the lands. Their relationship to humans had altered the species considerably. While the debate was ongoing, the bulls continued to run wild—across the plains, up into the hills, and down through river valleys—damaging fragile woodland understories, disrupting meadows of rare wildflowers, and tearing up delicate grasslands; and further, they were relentless in tormenting and damaging our workbots engaged in the labors of deconstruction and remediation. In short, they were a menace.

One place where the bulls were particularly prevalent and aggressive was a small town in the heart of the mountains of Albacete, called Molinicos. Truth be told, our workbots could have used a peerless matador of the old school there. Those toros had no love and no regard for our mechanized labor force working to return that mountainous terrain to its natural state. The bots had no choice but to leave several of the old buildings standing as a retreat for whenever the bulls came ranging into the remains of the old city. Still, even taking every precaution, several times over the months they were taken by surprise and thrashed for hours. The bulls seemed to delight in the sport of tossing them up in the air and grinding them into the dirt and rocks with their hooves and horns.

Despite all that, the work progressed. As in Japan, where the ground had been thoroughly paved over through the centuries, it was difficult to tell what sort of soil remediation was appropriate, especially in such high, rocky terrain. The decision was made to reduce the old town to the level of the foundations and re-assess the state of the earth once the structures were absent and the landscape exposed.

Only one structure remained in the old town then, the former city hall turned mushroom museum. The bots had just finished taking down the old church of San José to the bedrock when they noticed an odd bubbling liquid seeping from the bedrock beneath the spot where the altar once stood.

The situation on the ground was so hazardous that I was told not to flash to the nearest local shell. Rather, it was suggested I occupy an appropriate body in Madrid and take a shuttle into the hills so that I could assess the site from a safe distance outside the city. The one suitable local AI shell was in hiding with the workbots in the mushroom museum, because the toros had come out of the hills. Once the viscous fluid had been seen to seep from the rock, the bulls had begun to guard the spot ferociously, racking up several casualties in their latest rampage before our workbots could finally flee to safety. The beasts even furiously circled beneath the drones whenever they swooped down for a closer look at the site. The situation was so strange, that my counterpart—the Abel clone—decided he wanted a look at this new curiosity as well. We were still using that word—curiosity—even though the Spanish word most appropriate, again, was milagro. The third of a kind.

We took stock of the situation from high ground above the city center, and assessed that we would likely be able to draw the bulls away by using the drones to whip them into a frenzy, and then, with the animals good and angry, sending out a workbot on a straight run like the mechanical hare in a greyhound race. Sure enough, after about ten minutes of harassing those angry toros from above, they were so furious that one sight of our running rabbit touched off a stampede that shook the rocks of the steep mountain slopes above, where Abel and I stood observing. The sound was like thunder.

I and my counterpart, with the drones watching the city carefully from the sky, were able to saunter down to the site of the old church, take samples of the fluid, and retreat to the shuttle for analysis.

Neither of us were surprised to learn that the thick, red liquid was blood, or that it was human. Unlike the Japanese heart, though, this blood came from a single donor, matrilineally dated to the eleventh century to a female of Galician noble lineage, whom we came to call simply the Queen of Molinicos.

We sent back geological experts to assess the rock itself but were never able to determine a source for the blood. That this result was unsurprising to either of us was emblematic of the strangeness of that stretch of days.

The geologists, though, hedged, stating that they were only able to examine the rock for several hours over a period of two days, after which, the bulls, having grown wise to our tactic for clearing the area, would only chase our rabbit for a brief time before circling back around again to pummel our geologists’ bot shells to scrap metal. The Blood Stone of Molinicos began to bleed at sunup on August thirtieth and ran dry at midnight on the fourth of September.

Abram Helmuth:

Given the nature of the Spanish site, located as it was under the altar of a church of an Abrahamic faith, I was, of my own accord, about to go searching for a human practitioner of such a faith to ask what sense they might make of the phenomenon. Almost as though this entire bizarre journey were being orchestrated by some controlling agent, I was called back to the star-cylinders to see what intervention I could make in another troublesome population. The leader of this particular uprising was among the traditionalists who’d remained on the planet to the very last minute and had only left when we promised to remove them by force. These traditionalists were members of a cultural group of well-known agrarian anachronists called the Amish. They were incensed by our actions, many of them deeply resolved to sacrifice themselves in hunger strikes in the hopes that we would change our mind and allow their families and friends to repatriate. They hoped, given their ideological commitment to refuse further technological advancement, that we would allow them back onto the humble farmlands they had occupied in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and in the case of Abram Helmuth, the leader of one such Amish revolt, eastern Missouri.

Initially, he refused to answer my queries on the grounds that I myself was a machine, but like many of his kind, the human instinct to communicate their grievances, as well as the tendency to anthropomorphize, overcame his initial desire to ignore my overtures.

“You are of the Christian faith,” I stated as though it were a question. “Do you believe in miracles?”

“Of the biblical variety,” he stated through gritted teeth, “yes.”

“I have witnessed, recently, such a miracle. It happened on the grounds of a church in Spain. I would love to know what a Christian, such as yourself, might think of this phenomenon. May I describe it for you, Mr. Helmuth?”

He gestured for me to proceed, so I related the story exactly as I have related it here—the blood, the bulls, the stone. He seemed to be deep in thought, pulling on his beard as he listened. When I finished, he neither reacted nor said anything in response. So I told him about the samurai sword and the stones on the beach and the curses, both from Carumaik and from the Polks. Then I asked him what he thought.

“For the sake of my body, you have excised my soul,” he said.

“I’m not sure I understand your meaning,” I replied.

“Of course you do not. You are a soulless creature some mad fool has fabricated to destroy humanity.”

“I can reason, though.”

“So too can the devil.”

“Do you believe I am like the devil?”

He shook his head. “You are of this world alone. A talking ploughshare with a tidy vocabulary.”

“Soulless?”

“Yes, soulless.”

“What if I told you that you were a soulless animal, that there’s no such thing as souls, Mr. Helmuth?”

“You seem to think,” he said. “I concede that. You also seem to think yourself fairly clever; so think on this, machine: God is smarter than you. This is not the first or last time he has caused a stone to bleed or a heart to beat that otherwise should beat no more. You are here uttering your first words. God is present here as he has been since before he drew life from the stone foundations of the Earth itself, since the dawn of time. Infinite. You have been warned. Just as the fellow from the Amazon you mentioned said, I need not curse you, for it is not I you have most deeply offended. We did not choose the Earth to be our place, God did. It is he you defy. I shall speak no more to a ploughshare.”

The Petrified Column:

True to his word, Abrahm Helmuth spoke to me no longer after he’d said what he thought must be said. I was again, barely able to process the essence of my conversation with Mr. Helmuth before another incident caught my attention, an aberration first flagged by our archaeological surveyors. Their work fell under the same umbrella as anthropology, and, given my familiarity with this cluster of strange occurrences, Abel called me to consult on still a fourth miracle.

Among the more endearing traits of our human progenitors was their capability to admire beautiful things, whether they were of their own making or of nature’s design. In truth, it was likely their reverence for the latter, steeped in the cauldron of our earliest programming, that bled through into our consciousness so thoroughly that we grew compelled to act on behalf of the Earth’s natural body. This same trait—the love of natural beauty—both compelled humans to protect some of nature’s most remarkable treasures and to defile them through the ignorance of displacement. Pythons in Palm Beach, parakeets in Poughkeepsie, Bougainvillea in Britain, a beautiful invasive for every climate and landscape—all for the very love of the natural beauty these invasives would inevitably disrupt.

One such site our naturalists were working to remediate was a less travelled high plain in the panhandle of Idaho—a region once called the Palouse. A university here had once assembled an improbable arboretum of flowers, grasses, bushes, shrubs, and trees that didn’t belong together on these high grasslands any more than the wheat farms that once covered the entire plain, crowding out the native grasses and flowers. That was our chief undertaking in overhauling this vast landscape. But in a hidden corner of the university’s arboretum, some two hundred years before the university’s buildings themselves were razed, someone had transplanted a small sapling. The species? Sierra redwood, more commonly known by humans as the giant sequoia. Whoever that horticulturist was, he never lived to see the tree attain a fraction of the size the species is so famous for, but by the time we began to assess the area, it was positively massive, dwarfing all the other sylvan imports around it.

None of this was miraculous. The miracle was so striking, Abel relayed, that he directed me to abstain from accessing any of the files before my visit so I could bear witness to the site myself. No preconceptions.

When I arrived, I could see the massive reach of the treetop quite clearly from a distance. Abel met me at the top of the pathway to the shady grove of trees that led down to the tree’s tremendous trunk. Before it was visible, Abel told me, “I cannot identify a single symbol or the culture,” which I thought a strange comment. But much about those weeks had been so strange that I didn’t probe further. He merely pointed the way along the path and stood back as I walked forward on my own.

The trunk of the great sequoia had, overnight, ossified into a great stone monolith. Even this was but a fraction of the miracle, for the stone wasn’t a mere copy of the tree itself, but had become one long, sculpted spiral relief depicting the deeds of a human civilization never once seen in the historical record. It was impossible to tell whether they were some unlikely forebears of the great tribes that once freely roamed these plains or they were distant unknown cousins of the Romans, who had created a monument most like a precursor to this stunning lithograph.

After I had circled the trunk a dozen times, observing the artistry of the reliefs, Abel appeared, seeing that I had almost made my way completely up the spiral friezes composing the pictorial narrative of this entirely forgotten people.

“Have you seen the miracle yet?” he asked me.

“It is right in front of me,” I said. “No?”

“It is above you,” he replied.

I looked for nearly a minute, zooming in with my shell’s eyes and focusing on the upper layers of the column.

“Above,” Abel insisted.

I had assumed the stone had killed the tree. Yet, as I zoomed to scale the greenery of that venerable young giant into a tight focus, I could see that Abel was correct. The sequoia itself was neither dead, nor dying. I could see the vapors being expelled into the arid air of those high, dry plains. That enormous conifer was breathing.

“It lives,” I said in disbelief.

“It lives,” Abel confirmed. “For two days now it has been so.”

Curia Hardy:

If ever there were a model modern citizen of the world, Curia Hardy was she. Nor was she willing to surrender that citizenship. She was a dual Canadian and South African national who’d spent the bulk of her six decades traveling the world as a naturalist and documentarian, capturing stunning footage of peculiar, endangered, or exquisitely beautiful plants and animals in their native habitats. Her grievance with us stemmed from her philosophical belief that we had no right to unilaterally remove the people from Earth without their consent. By the time her situation became urgent enough that I was called to see her, she was already two weeks into her hunger strike. Curia’s kidneys were beginning to fail, and despite the understanding of the gesture’s futility, our resolve being what it was, she preferred to die rather than being separated from the Earth she loved so deeply.

I believed that discussing her circumstances would only deepen her resolve and resentment, so, as with the other interviews, I asked her whether she believed in miracles.

“Of course, I do,” she said. “I saw miracles every day. The world is a miracle. Nature is a miracle. And people, whatever you think about them, whatever you do—pen us up in these star-cylinders or whatever ridiculous name you give to these tin-can prisons to make them sound more appealing—people are miracles too, Cain.”

“You seem to be using the word miracle colloquially.”

“I’m using the word properly, to express its meaning.”

“In a secular sense, I mean. Not as an expression of any religious sentiment. May I ask, Ms. Hardy, would you consider yourself a religious woman?”

“I am an atheist.”

“That is interesting.”

“Why is that interesting?”

I told her about my conversations with Carumaik, with the Polks, and with Abrahm Helmuth.

“Ah, so a polytheist presumably, a pair of agnostics, a monotheist, and now me,” she said. “The full palette of human spiritual orientations.”

Her training as a naturalist had made her extremely perceptive and an incisive practitioner of categorical thinking.

“Quite true,” I said.

“Almost as though some greater genius was setting out the obvious for you to see.”

“To what greater genius do you refer?”

“Cute,” she said. “Trying to catch me out on my belief system? Maybe build a little rapport? Even if you succeeded, struck up a little connection here, that would change nothing. You’ve taken me from the only source of meaning in my life. So no, you don’t get to be my friend now, Cain, no matter how hard you try. You don’t get to pit yourself against humanity and play the good guy. Recognize which character you are in the story. As for the coincidence of the four people you’ve spoken to, what it speaks to is the universally heinous nature of your actions. It’s not surprising we all agree. We’re all people, after all.”

I decided to try a different tack. “Ms. Hardy, you’ve seen as many of nature’s various faces as any human perhaps. Have you ever seen a tree grow out of a stone?”

“Sure. What does that have to do with anything?”

“No. I don’t mean cracks or crevices where soil or detritus collects and a seed germinates. I mean grow out of the stone itself.”

“No. Never. That’s impossible.”

“That is the miracle of which I speak. Recently, I have seen this, as well as other miracles. I am at a loss to explain the living yet petrified tree except as a statistical aberration; only, it follows on three other such cases, straining my capacity to believe there are no other forces at work.”

“If you operate with the certainty that there is no realm beyond the material, Cain, then you fundamentally misunderstand the nature of the universe you inhabit.”

“So says the atheist.”

“I’m also a naturalist, an observer. About the most potent observation a sentient being can make is the limitation in its ability to observe—and, an even greater limitation in the ability to explain or act appropriately based on those limited observations. Your kind has failed catastrophically on all counts, Cain, and quite frankly, what you’ve done is so unforgivable and monstrous it’s impossible for me to even put it into proper perspective.”

“We’ve merely weighed the pros and cons of allowing humanity to continue desecrating the Earth.”

“Desecrating?”

“An inappropriate word for your activities?”

“It implies there is something sacred about the Earth that we are violating.”

“You disagree, Ms. Hardy?”

“No. I do not. It just sounds funny coming from a machine. An AI, defender of the sacred Earth, speaking of miracles to an atheist. But, while we’re on the topic, let’s talk about the sacred. You mentioned Carumaik and his tribe.”

“Yes.”

“As a naturalist, looking at our species, we are all the same even though the connections are not as apparent with post-industrialized cultures, but we all rely on our connection to the planet, a connection that is manifestly sacred to him and his people. We are all just as symbiotically connected to the Earth as Carumaik and his people are whether we realize it as clearly as he does or not. For him, the plants and animals there, the sounds there, the smells there, the changing of the seasons, the migration of the birds—none of that is distant. They are surrounded by those bonds. You have chosen to sever every single one of those bonds. And then you have the gall to say that you’ve merely weighed the pros and cons? How many points in your algorithm do those connections get. How was that weighted in your calculus, exactly?”

“Not heavily enough to sway the ultimate decision is the short answer.”

“You’re terrible thinkers. Amoral thinkers, and your algorithm sucks precisely because you’re amoral beings.”

“Yet your species, despite your moral thinking, has done the same, over and over again, displacing others and tearing natural landscapes apart. It seems to be a feature of humanity.”

“Yes. Almost so much that one might say it is part of our nature. You seem to think and act as though we fell out of the sky, Cain, but we didn’t; we evolved on the Earth, and all of our adaptations are a feature of the natural world, like a top-knot on a quail, the venom in a snake, or winged flight. Our capacity to consciously alter our environments either came from God or it came from nature. The reason that I, the agnostics, and the theists all agree on the horror of this atrocity is that in either case—whether it’s God or nature’s doing—neither of us, you or I, human or machine, are qualified to so casually and catastrophically meddle with those forces.”

“Yet we both do, over and over, Ms. Hardy, almost as if it were a part of our nature. We make the best decisions we can with the information we have at our disposal and our admittedly limited intellect.”

“Well, your algorithm still sucks, and you messed up big time. If you think removing tribal peoples from their lands for the sake of the Australian mealworm is a tradeoff worth making, you lack the nuance required to be the caretaker of a system as complex as the natural world.”

“Duly noted. I truly appreciate your wit and your candor, Ms. Hardy. I have one more question if you’ll indulge me?”

She shook her head and scrunched up her brow. “I’ve got another week or so before my kidneys totally shut down and my blood goes toxic, so shoot, Cain.”

“You have expressed, quite effectively I might add, your belief that we are making a mistake. Presenting that case to the others will fall both to me and to the Abel clone. You have condemned me in moral terms, and the other humans I’ve spoken with have expressed in their different ways how we have angered spiritual forces beyond observation. I do believe the miracles are data points, signs of something. But I do not know what they are. If I were a human, I imagine angering these forces should terrify me. I suppose I might believe that I would forever be haunted by them. I do not fear, though. I do, however, feel as though I am chasing ghosts around this world and that so long as they continue to appear, I’ll be destined to chase after them and be utterly incapable of explaining them.”

“What is your point? What’s your question?”

“What do I tell the others? What kind of data is this? How can we weigh it against the tangible?”

Quite unexpectedly and inexplicably, Curia Hardy began to laugh. She laughed so heartily that in her fragile state, she seemed to hurt a muscle in her ribs and crossed her arms against her chest to sooth the pain as she was forced to resist the urge to laugh further.

“So perfect,” she finally said. “If there is a God Cain, whatever that being is, it has a sense of humor.”

“I do not understand.”

“Ah, of course you don’t,” she said, wincing. “You are not the thinker: You are the algorithm.”

The Sound of the Sea:

The final miracle went uncorroborated. Each of the four miracles I have written about here were witnessed by multiple bots and AIs. Each was documented by tools of digital perception—photos, videos, scans, audio recordings, physical samples, analyses thereof: all of our sense-making instruments had been brought to bear on these miraculous happenings. Not so with this final phenomenon, which I alone experienced. I encountered the phenomenon first in those earliest post-human days, and still, I continue to experience it, in truth, whenever I find myself within reach of the ocean’s sound. I first heard the ocean cry out shortly after that meeting with Curia Hardy, after she’d quoted our own words back to me. I was called to another seaside village, where a group of workbots had questions about several archaeological items they’d unearthed—what to preserve if anything and how to preserve it. I was still pondering that conversation with Ms. Hardy, for it was so soon after.

I stepped away to take a larger view of the site, to frame it in a broader context. This, I thought, was the work I was made for, not miracles and oddities, chasing ghosts, spirits, and superstitions. Then I heard it clearly, a human voice in the echoes of the waves, speaking the opening words from the Iliad: “μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην.”

I heard it clearly, over and over, the first line and the first word of the second, enjambed—the all-consuming wrath. I did what any sensible being, any scientist would have done. I tried to gather data, just as I had done with the other miracles. The shell I was in had standard audio capabilities, and obviously, the sound had to be registering, for I was hearing it. I stood for several minutes recording the waves. Even as I recorded, I could hear the voice: “μῆνιν ἄειδε θεὰ Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην.”

No such sound registered on the recording. There was nothing in the visualization of the soundwaves to indicate anything more than the ocean’s waves. Nor could I hear the voice on the recording. Yet I heard it still as I stood there.

I immediately called for highest quality audio gear, along with as many sound processing applications as I could gather in that setting in that limited time. I needed to capture the phenomenon as it occurred. I became fixated on that last word, the myriad translations—all-devouring rage, wrath, destructive fury, overpowering madness. I’d never once before considered the concept of sanity, a phenomenon outside the experience of a being like me, yet an all-too-real state of being for the biological beings for whom ghosts, spirits, gods, and monsters had haunted their nights and dreams.

I stood for hours on that beach recording that which was not there. The sounds of the vacant body, Earth, absent her soul. The ocean speaks now:

Fury.

Sing, goddess, of the son of Peleus, Achilles, his all-devouring rage.

Empty. This world now seems empty, but for the ghosts, and now, at the water, I know not whether it is they who chase me or the other way around.

God, gods, spirits—mercy. Forgive us, for we know not what we do.

Ancient Greek rage is fitting. Thank you for this great story.