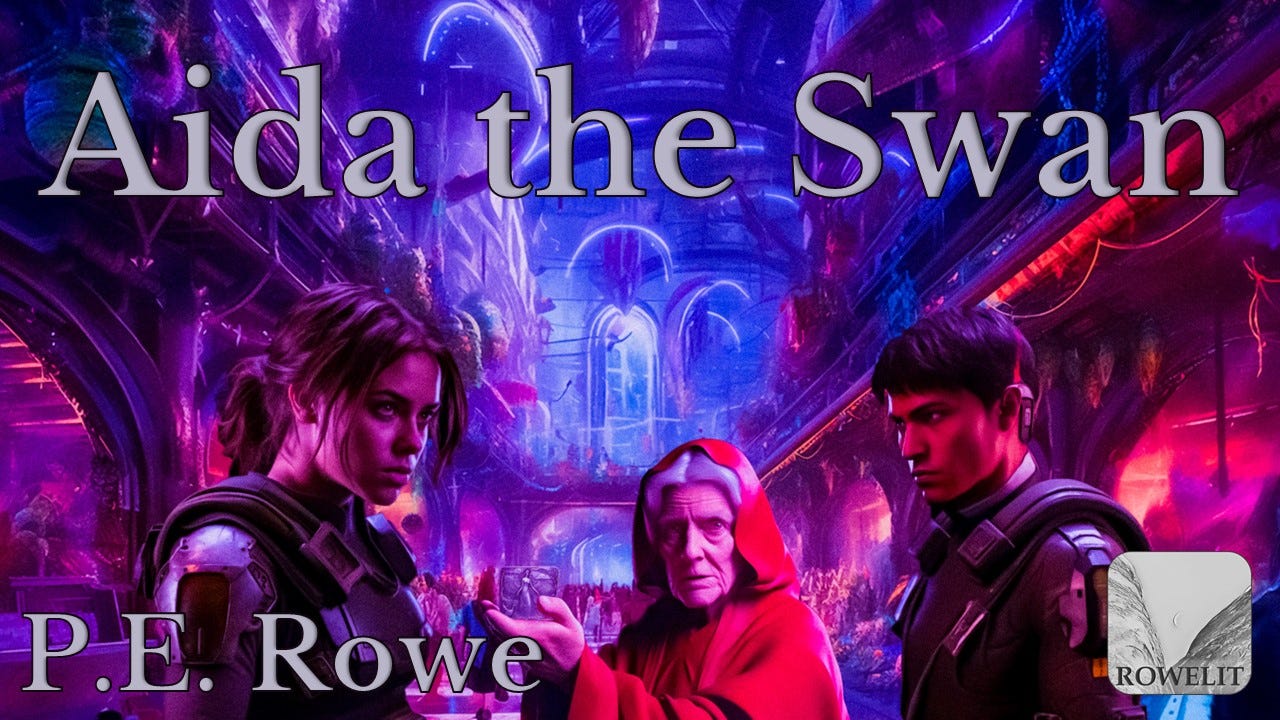

Aida the Swan

“If you do not choose your own god, someone else will choose it for you, and you may not like the outcome.”

ONE YEAR AFTER THE BLAST:

For Endamo Dalegash, a surgeon of the Semmistratum, happy endings were fleeting. From the moment he’d first set eyes on the woman he’d come to visit, the burn victim from Kendry, she was never a candidate. She’d been in the kill radius of the blast that had leveled the city of Maddutz on the independent world of Kendry. The team that had pulled her from a blasted out concrete stairwell had administered medication as much to ease her passing than to offer any hope of recovery, for there was neither recovery nor comfort for one so far gone as she. But the woman had refused to die. She had been so badly burned that it was difficult at first to tell she was even human, yet she’d hung on. Dr. Dalegash couldn’t imagine what she’d gone through. After looking over the rescuers’ footage and thinking back to his first sight of her, he couldn’t fathom the message he’d received from the doctor on Tressia—that she was alive, for one; whole, two; seeing better than she’d ever seen, three; and even remembering small things from her past. Speaking. Hearing. Endamo Dalegash didn’t often think to use the word miracle, but this woman from Kendry surely was one if the doctors on Tressia spoke truth.

Dalegash served aboard a hospital ship, the Nexus, which moved into hot zones as soon as it became safe to do so, sometimes before. Their mission—the movement’s mission—was to save as many lives as they could, which was a far smaller number than anyone in the agency would have imagined before seeing the war with their own eyes. Radiation got many of them. The accumulation from trauma got most of the rest. The reality was that the Semmistratum treated many of their patients when they were already actively dying. Usually, little could be done but to offer some hope of comfort and company in their final hours—a human touch. It took a special person to volunteer for that kind of work. It was still a marvel to Dr. Dalegash that there were any such people in the universe. That was what gave him hope more than anything, but it was surely a blessing any time he heard that someone beyond hope had come back.

They’d called her the swan. The blast had incinerated her clothing, stripping her gear from her body. They’d suspected she was a soldier by the upper from a boot, but she had a solid metal prayer iconograph from Tressia fused to the burnt skin of her breastbone directly over her heart. Dalegash couldn’t say it was this shield that had saved her heart, but the thought had occurred to him. The figure on the prayer card was a swan. It was a nurse from Kappa-Ostia who recognized the iconography as part of the religious tradition of the Tressian people.

“That’s Leda’s icon,” she said, after she was shown the prayer card. “The swan has always been Leda’s symbol. She must be a Tressian.”

Dr. Dalegash did wonder what a Tressian would be doing on Kendry, but there were peacekeeping forces there. He had little reason to object when they’d added “Leda” in parentheses after Jane Doe on her chart. She was probably going to die anyway, better to die with the wrong name than none.

Leda never regained consciousness in his presence. Their charter being what it was, the Doctors of the Semmistratum were prevented from using the more radical nanotech interventions the Tressians were known to experiment with. Tressian doctors also did revolutionary work with regenerative genetech—to the extent that they were rumored to re-grow failing organs, but it wasn’t the woman’s organs Dalegash was concerned with. Her brain would have suffered extreme trauma followed by an afterwash of radiation so potent, he figured there was little beyond brain stem activity and chaotic neuronal firing. Who knew what had been going on in there.

The Tressian doctor who’d called him to visit, Kinsley Amiro, had asked Dalegash to meet them at the vassur in Hieira, a smaller city on the southern continent. Vassurs, he was told, were temples in the Tressian network of holy sites—the home of a small army of Tressian holy warriors dedicated to the protection of humanity. They hadn’t taken a side in the war, but would, whenever possible, intervene to protect neutral sites, evacuating them before disaster struck. That was as reasonable an occupation for their mystery woman as any.

The Hieira vassur had a wide, imposing façade, with a long row of statues of Tressian holy warriors facing out toward the city at attention. The structure could not have been older than a century, but it bespoke millennia of tradition, hearkening back to Earth even. Dalegash followed the light trail Dr. Amiro had messaged his glasses earlier that day.

“We’ll be waiting for your in the upper dojo.”

He hadn’t been part of the transfer team that brought the woman down to the planet, so Dr. Dalegash had never met Dr. Amiro before. She looked like a lovely young woman on her profile but he wasn’t sure he’d be able to pick her out of a crowd.

As he entered the viewing area in the upper dojo, Dalegash was surprised to see a sizeable audience standing in observation of the weekly rites in silent reverence.

On the center mat, there was a woman fighting an adapted Andrew, both using long staffs as weapons. Judging by the speed and precision of the movements, the woman may well have been an android too for all he knew, but Dalegash couldn’t recognize the model. And she looked too human. The fighting was fiercely beautiful, the speed of it shocking to an eye unfamiliar with violence. Still, the movements were measured, purposeful, flowing, punctuated by the sound of the two staffs clapping against each other repeatedly. The woman was light on her feet, and occasionally, when the Andrew seemed to have her on her heels, she would pivot back on her staff, flipping away, rolling, and coming back to attention as the Andrew pressed in. Finally, she managed to snap the Andrew’s staff, leaving him holding one half of the long stick, and set as he must have been to a deliberate performance level, she was able to clap the android about the knee, slap the other half of its stick away, and stop just short of landing a destructive blow up the side of its head, ending the session. Never before had Endamo Dalegash understood why they’d called them the martial arts. This, he thought, was not so far from dancing. The young fighter was sensational.

“Dr. Dalegash, there you are,” Dr. Kinsley Amiro, whispered to him, approaching him from behind. “I’m so glad you got to see her perform weekly rites.”

“See her?” Dalegash said, gesturing to the mat. “Leda? That was her?”

Dr. Amiro nodded. “She’s remarkable, isn’t she?”

Dr. Dalegash’s mouth hung open, his eyes straining to get a closer look at the young woman he’d just been marveling at. He couldn’t quite reconcile the idea that she was the same person who’d come to him all but dead, burnt to the bone in places below her knees—yet those same legs had just performed the feats he’d marveled at.

“She would like to speak to you when the celebrants are dismissed.”

Leda’s two doctors stood in silence for nearly an hour more before the weekly rites were concluded. For Dr. Dalegash, who’d never been anywhere on Tressia before, it was an experience he could scarcely believe. To see the human body do such things, all to simulate the most atrocious of human behavior. He didn’t know how to feel, finding beauty in the entire spectacle.

The woman who approached them after the rites was a stranger to him. She looked younger than he’d have imagined—mid to late twenties, with dark brown hair. She was striking, quite beautiful herself, which he’d had no way to guess from the state she was in last he’d seen her. She extended a hand to him.

“Dr. Dalegash,” she said as she shook his hand. “You kept me alive.”

“I can’t take much credit for that,” he said. “You had far more to do with that than I.”

“But you brought me home,” she said, “so I could be treated.”

“Many more than myself helped you along the way.”

“And I wish I could thank them all. I do remember a nurse who sat with me for many hours over many days. Kira? Akira?”

“I knew a Mira. She did sit with you once, but I don’t recall her caring for you more than that.”

Leda looked disappointed. She took a deep breath.

“Remember what we talked about with memory,” Dr. Amiro said. “It’s okay if it’s hard.”

Dr. Dalegash looked inquisitively at his colleague.

“Her memory, her identity. What you saw on the outside was not unlike the trauma her brain endured.”

“You look wonderful,” Dr. Dalegash told her. “I’m delighted to see you, and even more delighted that you see me.”

“Right-side up too,” she said to Dr. Amiro, clearly a joke that was lost on Dr. Dalegash.

“Have you had any luck finding out who your people are? Family?”

“We’re still working on that,” Dr. Amiro answered on Leda’s behalf. “We haven’t been able to find a link in the gene network yet.”

“I’ve been recovering here,” Leda said. “They won’t let me rejoin a unit until I recover my memory.”

“They may never,” Dr. Amiro interjected. “We’ve talked about this.”

“I’m a pilot,” Leda said to Dr. Dalegash. “I remember that much. From a special forces unit.”

“I don’t doubt it,” he said, gesturing back toward the mat. “It is a thrill to see you today.”

“Please, Dr. Dalegash, I know she couldn’t come down herself, but I would like you to thank Mira for praying with me. You might not be aware, but she was with me more hours than I could count. She kept me going. Please tell her how grateful I am. To you as well. I’m alive today because you brought me home.”

“Many are not so lucky,” he said. “So I am grateful to you for calling me down. You have no idea how wonderful it is to see you beat the odds. I wish you all the best in your journey forward.”

She clapped her hands together and bowed, looking Dr. Dalegash in the eyes. For a moment, he could see her there, the bone structure, the burnt skin, hairless, eyeless, the features of that anonymous skeleton, barely clinging to this plane of existence with each wheezy breath. As he pressed his palms together and returned the gesture, he wondered who this beautiful person could be.

EIGHT MONTHS AFTER THE BLAST:

For four days she had been staggering around the ward with a Harold on each arm to catch her when she lost her footing. Dr. Amiro had never seen such determination. This young woman they were calling Leda was turning back into a person, maybe like she’d read about with a chrysalis, the beautiful being emerging from that burnt husk. It was not without struggle.

The ocular specialists had re-structured the dermal layers around her orbital bones, which had been all but burnt to the skull. Their senior fellow had grown her new conjunctival tissue from hybrid stem cells and built her designer eyes to her specifications. She’d claimed, even before she could hear again, when she could barely whisper, “I’m a pilot.” So the top surgeon asked her about features—the ability to zoom, focus, see outside the normal spectrum, in darkness—anything a biological eye could do, and even a few features that were only possible with nanotech. Then, he’d cross-wired them in relation to the optic nerve.

“It’s fine,” he’d told Dr. Amiro. “Give it a few days. Her mind will flip it right-side up.”

Leda was beside herself.

“The room is backwards,” she said, gasping at her first sight in nearly half a year. “It’s blinding…”

She stopped for a moment and screamed, “No!”

“What’s the matter?” Lansing, the ocular surgeon, asked her.

“Everything is upside down!”

“Your mind will make it right. It just needs time to adjust. You are seeing, though?”

“Yes. I’m seeing everything wrong.”

Her head was pitched all the way up at the ceiling above him.

“Look up toward the floor,” he told her. “And tell me how many fingers I’m holding down.”

Almost instinctually, she obeyed that contradictory command and stared directly at his hand.

“I can see every line in your palm,” she said, marveling at the sight taking shape in her brain, “and you’re holding four fingers down.”

She tried to tip her head to right the image and nearly fell off the bed.

“Whoa, Leda,” Dr. Amiro said, stepping forward to catch her.

“It’s all wrong,” she cried.

“I can order a pair of glasses,” the ocular surgeon stated, as though there was no problem at all. “It’ll flip the image before it enters the retina. If that’ll help reassure her that it’ll be okay. The brain will do it on its own though. And if she gets used to the glasses it’ll take longer.”

“You’re sure?” Leda asked.

“One hundred percent. I’m not even the least bit concerned. This is great news. You’re seeing just fine.”

Her face betrayed plenty of doubt.

She was being transfused daily with signature blood and plasma the hematologist was growing from her own cultures. It was designed to take root deep in her bone marrow, turning her own bones into a factory for the nanites that were healing every cell they perfused, delivering microscopic repair through her own vasculature to every area of the body recovering from the trauma of the burns and radiation. They could heal her once, yes, but the level of radiation she’d endured would mean chronically recurring cancer if there wasn’t a steady mechanism for cellular repair. Once the nanites set in, though, she’d likely never need to see a doctor again.

Dr. Amiro found Leda one morning in a terrible state, emotionally distraught. The nursing staff on the night shift reported that she’d suffered a long night, filled with nightmares, chills, and disorientation. They’d had to assign a Harold to sit with her to ensure she didn’t harm herself in a paroxysm of what the nurses had described as instinctual recoil from revisited trauma. Dr. Amiro went in to talk to her while they were waiting for the psychologist to arrive. Leda was looking down at the blanket covering her legs.

“It’s me Kinsley,” Dr. Amiro said. “I wanted to come talk to you. They told me you had a difficult night.”

“I’m still getting used to what everyone looks like,” Leda said, “upside down no less. My dreams are oriented correctly. I’ve been trying not to sleep. It caught up with me.”

“Are you remembering things from your life before?”

“I’m remembering after. I get trapped in time.”

“Trapped in time? What do you mean.”

“I think the part of my brain that registers time must have broken. Somehow, I’d forgotten about that, Kinsley. There are pockets of memories that I’ve been finding in my dreams, dark and black and filled with ages of time just awash in pain. I don’t know how deep they go.”

“Can you try to visualize something there? Any images from your life?”

“The only thing I know for sure is Leda. That’s the only thing that feels familiar to me—the sound of that name, my name. Everything else is a jumble of sensations. One of them is flight. The other is pain and darkness.”

“Dr. Sam, the psychologist, is on her way. She can help you put some of these sensations in order better than I can. I just wanted you to know I’m here if you need anything.”

Leda was clutching the metal prayer card in both hands. “I’d rather see the chaplain if you don’t mind.”

“Perhaps both?”

“Both, yes,” Leda said. “There is more than me there. Something deeper, and I don’t know what to do about it.”

“I don’t think any of the monks come down from the vassur until tomorrow, so Dr. Sam can get you started. We’re still looking for your family here on Tressia, Leda. We’re not going to stop until we’ve checked every last family in the database. Then we’ll look for ex-pats in the independent systems and the Letters. We’ll find your home. We will.”

FIVE MONTHS AFTER THE BLAST:

When the Semmistratum brought her in, the woman was in worse shape than perhaps anyone Dr. Amiro had ever seen. It was almost impossible to believe that she was still alive. There had to be something immensely powerful inside of her, keeping her heart beating. Her lungs, rose and fell to the beat of the ventilator bedside. With her absent eyes, covered over by a white cloth bandage, it was nearly impossible to tell the difference between this woman and a braindead patient whose body was on life support. Every so often, though, the woman would flinch, as though a jolt of some sensation had overtaken her limbs, and she would push a moan through the ventilator tube.

The Semmistratum called her Leda. All she had on her person when they’d found the body was a metal prayer card of the kind produced in the western states, near Edgi-Gabron and Mappur, the deeply religious splinter colonies, where parents with large families sent many of their children off to the vassurs to be raised in the holy warrior tradition. This woman, Leda, bearer of the swan icon, was certainly a defender of humanity. Some of her kind worked alongside humanitarian groups, providing cover when they went into hot zones. Some went into the independent systems to evacuate refugees, even to stage defenses of planets the Etterans and Trasp had no cause or claim to aggress against.

Dr. Amiro recognized the telltale signs of liquefaction in the woman’s tissues, radiation sickness that would have killed her if not for the Semmistratum’s interventions, but those doctors, heroic as they were, would not have healed this woman. Even in the western regions of Tressia, they’d have taken her for a martyr and allowed nature to take its course. Dr. Kinsley Amiro was not trained that way, though. This warrior for humanity could do no more to lessen the pain of the war once she died. She could treat Leda, and if all went well, maybe even heal her, but Dr. Amiro could only wonder what was going on in the mind of that poor woman as she came back slowly from the brink.

Time, it seemed, was non-existent, or at least not linear. She was in a building most of the time, struggling to find the exit. The sun burnt her skin when it found its way into the corridors through the large bay windows. She didn’t recognize the city or the world, but it had to be a domed city, for the starlight scorched her skin despite the radiation shield. If she was going to get back home, it would have to be at night.

Most of her day, she was searching. A way out. A familiar face. A clock. Time was important. When was sundown? She couldn’t go out into the halls. She spoke with a woman from a colony that didn’t exist, at least to her recollection, Alpha-Omar. Omar was just a friend she’d known long ago, but she couldn’t recall from where or even his face. This woman she spoke with—Aida—told her that she had been dying for the last thousand years and was trapped in purgatory. According to her, the light would hurt, but it would set her free. None of that could be true, because if she were dying, there would be nothing in this space. She got stuck in another apartment with a tortoise. It would have been easy to assume he was mute, but, if she was patient and waited for the sentences to form, she could understand him. The tortoise was wise. He told her that all reality began with perception. Her reality was here, now. The memories of her dreams could never be measured from here. Only the now existed. The universe began and ended with the mind, which began with the brain. The tortoise asked her where her brain was. “In my head, of course,” she said, only to realize she could not feel her head. She could not feel anything, except the starlight. She had been in that room forever. Then the tortoise told her the light would set her free, that time had to exist in the light.

Odds were good, she thought, that the light would set her aflame and end her. But she had to trust that her death would mean something. She wanted to ask the light what time it was now.

Dr. Amiro had to adapt the neural actuators to the sensitive skin on Leda’s scalp. Otherwise the device could open wounds that would hinder the slow process of healing the woman’s dermis. Reading her thoughts was a curiosity to assuage the medical staff’s fears—what was this poor woman thinking, feeling, fearing while trapped in that burnt-out husk of a body? Did they even want to know, after all?

Dr. Amiro spent nearly two days with two Harolds assisting, trying to fine-tune their sensor network to communicate with this unfortunate holy warrior. She wanted to send the woman a simple message: “We are here with you. We are going to help you.”

This Leda’s eardrums had been blasted into little but a ring of scar tissue. Dr. Amiro thought she could whisper directly to the woman’s brain using the actuators and then listen for a response from the frontal lobe. She sent one of the Harolds to sit with the woman to wait for a response. For days, there was nothing. It took time for the nanites to replicate and repair. Finally, the Harold called Dr. Amiro and told her Leda was speaking.

Dr. Amiro entered the room, hoping that there was some sign of coherent thought, that all this effort to save this woman wasn’t more harmful than good.

“She’s making little sense, doctor,” the Harold reported. “All she does is ask about the time, three or four times a minute.”

“Did you tell her the time each time she asked?”

“Of course,” the Harold said. “It’s as though she doesn’t hear us, though.”

But the time has been the same for years now, she thought. Even in the burning light, the time never changes, same minute, same day. That is the way. This place might be purgatory, after all. Does it even matter what time it is in purgatory? It never ends.

TWELVE WEEKS AFTER THE BLAST:

Dr. Dalegash was growing increasingly troubled by this woman from Kendry. She had been sequestered in an oxygen tent for nearly a month. No one had any idea who she was or what she’d been doing on Kendry. Her DNA wasn’t in any databases from the Letters or any of the independent systems the Semmistratum communicated with. She wasn’t improving, and she wouldn’t die. He had to wonder what was keeping her alive—beyond the ventilator and nutrition they were providing. Nature would have taken its course weeks prior had they allowed it to. There was an oath to uphold though. This charred person was still a person, even if her brain had been functionally liquefied by the radiation. All her other organs had been, yet here she was still.

Most of Dalegash’s patients who lived past the first few days were off the ship within a few weeks. They would be stabilized, treated, and moved out, often so effectively that they needed little more than rehab when they were discharged to a port of convenience. Dalegash took pride in being able to move patients from that traumatic phase of their life to a time of rebirth, or at least recovery. Most patients were resettled with distant family on other systems. Some were taken in by good-natured individuals, others by programs run by charities or governments. Dalegash knew of a few cases like this woman, but it was rare. All he saw in front of this woman was an indefinite confinement to that bed aboard the Nexus unless they could figure out an identity, or at least a nationality. If they couldn’t find her genes in any database, the only clue left was that metal plate she’d come in with.

Dalegash didn’t have time in his day to find the answer. He assigned a Harold the tedious task of showing the woman’s metal plate to every last person aboard the Nexus to see if anyone had any idea of its significance. His hope was that somebody could make something of it, perhaps assign enough meaning to it that they could justify getting the woman to the next step on her journey.

The Nexus had twelve hundred people on it. The Harold estimated it would take four days to query everyone about the metal plate if he respected everyone’s sleep schedule.

On the third day, the Harold returned to Dalegash’s unit with a nurse named Mira.

“Where did you find this?” Mira asked him, holding up the mystery woman’s only possession.

“I removed it from the skin above her breastbone, fused to her chest.”

“She’s Tressian,” Mira declared.

“So you know the significance of this metal plate?”

“It’s a prayer card. I’ve studied them in classes, but never seen one before. Tressians have a very complex religious tradition that descends from a peculiar sect of theists on Athos.”

“Are you from there? Nearby?”

“No. I’m from Kappa-Ostia. Tressia is quite a distance from us. I studied their religious traditions and symbolism as part of my course of study before settling on nursing. I have some training as a chaplain. Tressian holy warriors take an icon and wear it over their heart. They choose their godhead, as they believe that all forms are connected parts of the same one god. It’s almost like choosing their own guide or path of expression in their faith. This one, Leda, is from the Greek tradition. She is a consort of the divine, the mother of Helen, who weeps for the mortality of her human children.”

“Oh, that’s great news,” Dalegash said. “That gives us a chance to get her back to her people. I don’t know anything about their religious tradition, but I do know about their medical tradition. They’re aggressive with nanotech. They might be able to help her more than we can here.”

“I don’t know anything about that,” Mira said. “Just that she’s definitely Tressian. Would you mind if I went in and prayed with her?”

“No, of course not. If you’re confident you know her traditions well enough to be respectful of them, I’m sure she would welcome your presence more than the Harold I have sitting with her most of the time.”

“It would be my honor,” Mira said. “I’ve never met a holy warrior before.”

“When you’re finished, Mira, I’d like you to report what you’ve told me to the commander. I’d like to start the process of getting her discharged home as soon as we can. The sooner she’s back with her people, the better chance she has of finding peace.”

TWO DAYS AFTER THE BLAST:

Douglas didn’t care what McKenna had to say about it. They were going. It had been a long day on Kendry, scouring the blast zone for any signs of life. A forward team of guardians like theirs came days before the real heroes, at least in Douglas’s opinion. His team usually flagged as many dead as they could on the overlay, mapping the ruins to the best of their ability. In a few days, though, the searchers would come with an army of drones and bots to find as many dead as they could, and they would make sure a human hand would see each person to a proper rest. That work was the real thankless job. At least Douglas’s unit had a chance to save someone each time they went out. They often did. Not usually this far into a kill zone, but physics was funny, overwhelming but peculiar. Douglas had seen buildings of solid concrete and steel crumble to dust and mangled metal directly beside lighter spurs of nanomaterials and glass that stood tall after bending like a reed through a nuclear apocalypse.

They’d cleared three-quarters of their assigned territory from zones 43-32, and they’d found few dead, much less anyone living. And the closer they got to the center of the grid, the less likely it would be to find anyone left alive. The way Douglas saw it, they were getting a jump on the searchers and the recovery teams, lightening their load. McKenna saw it differently. If they weren’t saving people, they were wasting their time, risking exposure, and using up valuable emotional capital, which was an interesting argument he’d been forced to wrestle with in the months since McKenna had joined Douglas’s unit. Doing work like theirs, McKenna believed, was so emotionally draining that a person could only take so much of it before they were tapped out. Douglas had seen the truth of that belief in many of the older guardians who’d fled rescue for less depressing assignments. It was McKenna’s philosophy when they had days like this, on Kendry, that they call it early, when they hadn’t found so much as a body in an hour, and save that emotional capital for days they might find a purpose for their skills, rather than rooting around hopelessly so deep in the kill radius.

Douglas got a ping from one of the drones up ahead. The infrared signal indicated it could be a body. He pulled up the location on the grid. It was deep in the kill radius, nearly ground zero. But such things were only probabilities. They couldn’t account for materials science, the randomness of chance, the layout of the landscape. Douglas knew McKenna would gripe the second he gave the order.

“What do you think we could possibly find up there?” he asked Douglas.

“We’ll find what we find,” Douglas told him. “Look on the bright side. If we clear it, we’re one zone closer to finishing for the day.”

Douglas called the carrier down and picked up a small team—himself, McKenna, three Harolds, a pair of tunneling bots, a snake, and three drones, all with swarm capability. Then they flew up to Zone 33 to take a look.

At the site, there was little left of any structure on the landscape. The blast had turned solid structures to dust in an instant, and blown out that dust in a great burst of nuclear wind.

The remaining shard of an artifice was a leaning, jagged frame of a structure, extending into the dull gray air nearly thirty meters like a lone dagger protruding from the ground. There didn’t appear to be an opening, but there was an infrared signal deep within the rubble.

“Probably a battery caught fire,” McKenna said.

Douglas gave the order to send the swarm and the snake. The swarm were bee sized drones most commonly used to pollinate in ag cylinders. The Semmistratum had adapted them for search and rescue, because they had all the right properties. They were tiny, could fly into difficult places and then crawl around, taking footage and readings. Even more useful, they could form a chain to create an unbroken network relay so that their forward units could always maintain connectivity with the outside, no matter how deep they went into a pile of rubble like this mess in the heart of Kendry’s capitol. Once they found the hot spot, the snake would scout a possible ingress if Douglas had reason to think it was a person.

It didn’t take long for him to determine that it was. The victim wasn’t too far into the building, having been blown, it seemed, back into a stairwell that would have been closed to the outside but for the door, which had quickly been occluded by debris from the disintegrating building. The doorway was packed solid with debris to the extent that the swarm of tiny drones only found a few points of access. It was pitch dark in the stairwell, but once inside, there was a pocket of space where the outline of a body was clearly visible on infrared. A woman, by the size and shape of her body, still breathing. The image was punctuated by the clear thermal resonance of a heartbeat, pulsating warmth through her dangerously cooling and slowing body.

McKenna was dead silent.

No human could get in there. That’s what the diggers were for. Their talent was tunneling by creating hypersonic disturbances beside their outer shell, liquifying the rubble. As the diggers moved through the pile, their trailers supported the growing tunnel with polymer rings that snapped open to the diameter of the emerging cave. Douglas got an estimate of forty minutes to open a passage, package the patient, and return her to the carrier. The Harolds, as always, would do the dirty work.

It was always difficult for Douglas and McKenna to tell what the other was thinking, covered as they were in layers of protective gear. But at a time like this, it didn’t even have to be said. The hell that poor woman had endured must have been unspeakable. So they didn’t speak it. They sat breathing beat for beat to the gravity of the moment.

The scans the Harolds returned revealed three fractures of the long bones and several fractured ribs, but somehow, miraculously, no punctures in her lungs, which surely would have killed her long before their arrival.

Douglas and McKenna watched as the Harolds packaged her. There was hardly anything left of the woman’s tattered clothing and just as little remaining of her outer layers of skin. Had the heat dissipated any faster from the blast over the two days since, she’d have died already of hypothermia. Douglas didn’t say it, but her survival was through such impossibly long odds, it seemed providential, and he was not a believer. He came from a colony of them, though, and understood how they thought. There were many of his people in the Semmistratum.

“She has a metal plate fused to her sternum, sir,” one of the Harolds said. “It seems to be affixed to the remaining skin underneath.”

“Leave it for the surgeons to remove,” Douglas said. “Cover her up fast and get out here. The sooner we get her to the ship, the sooner she gets definitive care.”

“Roger, sir,” the Harold said.

Soon after, they’d packaged her in a sealed tube stretcher, which would ensure a supportive temperature and high flow oxygen while protecting the rescued woman from the fallout.

Once they had her out, and the Harolds walked the pill box over to the carrier, Douglas took a final look at the readings. She still had a heartbeat. He took a look through the video inside his helmet at a body that wasn’t nearly the worst body he’d ever seen, it was just the only one he’d ever seen that badly burned where the person still clung to life.

“Secure for flight,” Douglas declared. “Let’s double time it back to the shuttle. This woman’s alive, McKenna. She’s still alive.”

McKenna didn’t have a word to say.

MINUTES BEFORE THE BLAST:

There was a sharp ping in the captain’s ear—a proximity alert. It was impossible to know where they were or how long she had, but the Etterans were in the system.

“Hold here,” Captain Jemeis said to her top lieutenant. “I’m going after them. I want you out of here the second I order it, with or without us.”

“Thank you, Captain,” Admiral Carter said. “I won’t forget this.”

“If the Etterans get here before we take off, there’ll be nothing to remember,” she said. “When my lieutenant tells you, Admiral Carter, I need you to message your niece so we can get a fix on her signal.”

Then Captain Jemeis turned to her junior lieutenant. “Koss, you’re with me.”

She led him down to the gear hall. They geared up, put on their drone suits, and headed toward the back ramp. Admiral Carter had given them a location for his niece’s building, but she hadn’t been there, and the Admiral wasn’t going to allow Captain Jemeis to take off without her, not unless the attack was imminent.

“I want you in the air the second we get a fix on her,” Captain Jemeis said over the com to her top lieutenant.

Koss knew what to do. They flew out toward the niece’s building in the heart of the city. Vish’s unit had cleared it a half hour before, but if Carter’s niece was anywhere in the city, odds were she was close to home.

“I’m in place, LT,” Koss said.

“Hover there, Koss,” she said. “I’ll be in position in a minute.”

The niece’s apartment was in an older building about thirty stories tall, tucked within a dense neighborhood of other similar residential buildings.

As soon as she was in position and Admiral Carter called, Captain Jemeis got a ping back from the niece’s building. They’d triangulated her position on the third floor.

“What is she doing, Aida?” Koss said.

“Thinking like a civilian,” Captain Jemeis said.

She surveyed the neighborhood for a place the ship could set down. It was a hellish scenario. These people weren’t hardened like back home. They were all civilians like the admiral’s niece. They had no idea what an attack might mean. The structures were too tight together for the ship to get close. Aida’s first thought was to call in the ship to hover above the building and air-evac the admiral’s family through the window, but looking down on the streets and courtyards, gave her pause. Koss knew what she was thinking.

“They’ll all panic if we pull them out the window,” he said. “What do you want to do, Cap?”

Aida ordered the ship to touch down in the park a kilometer south of the building. Even if an evacuation had been warranted, there weren’t nearly enough ships in the system, and with the proximity alert, if a strike was coming, it was coming too soon to make a difference. If it was a false alarm, though, or—what was most likely—a symbolic retaliation, the panic over an incoming assault was liable to cause more fatalities than a few incendiaries worth of retribution for Minnara.

Captain Aida Jemeis and Lieutenant Carey Koss landed outside the building and proceeded up the lift to level three. The young mother opened the door and was completely shocked to see two ariel commandos in drone suits standing by her door.

“We’re here to evacuate you and your daughter,” Captain Jemeis said. “We need you to come with us now.”

“My husband?” Admiral Carter’s niece protested.

“Right now, it’s just a precaution, ma’am,” Koss said. “You were told to report to the airfield with your daughter. Where is she?”

“I object to all of this,” the woman said as Koss pushed past her into the apartment.

“If this is so urgent, then I’m not going anywhere without my husband.”

“Ma’am,” Aida said. “It’s urgent because your uncle is a strategic asset, and he’s refusing to leave without you and your daughter. If you have a problem with this, you can discuss it with him momentarily—the second we have you aboard our cruiser.”

“What’s going to happen?”

Aida could see it. The woman was starting to pick up on their urgency.

“Something’s happened, hasn’t it?”

“We think they’re targeting him because of Minnara, and we have cause to think they may have found him at this location.”

“All of our friends are here.”

“Ma’am, we need to go now.”

“I need to—” she started to pull back toward the apartment.

Captain Jemeis grabbed her wrist. “No time,” Aida said. “Koss! You got the kid?”

She heard screaming over the com.

“Could use a hand here from mom,” Koss said back.

They both headed back into the apartment, upstairs to the girl’s bedroom. Aida found Koss with his helmet off trying to console a crying seven-year-old girl.

“What’s her name?” Koss asked.

“Helen,” Carter’s niece said.

Aida, having just removed her own helmet to talk to the girl, looked back at the mother as if in disbelief, “Helen?”

The mother nodded.

“Okay, Helen,” she said. “This is my friend Koss, and we’re going to take you and your mom for a ride on our spaceship. Your uncle, Admiral Carter, is going to be with us too. But we have to go now.”

“Not without my capras,” the girl said.

By that time, her mother had knelt beside her and had begun to try to explain the urgency.

“It’s what we came back for,” Carter’s niece said. “That and a change of clothing.”

Aida Jemeis gestured as though to ask what the girl was talking about.

“They’re figurines—dolls,” the mother said. “They’re very special to her.”

“Where?” Aida said.

The girl pulled away from her mother and opened the wall cabinet with a wave, revealing a huge collection of the dolls.

A second proximity alarm blared in Aida’s ears. “Upper atmosphere, southern continent,” the top lieutenant stated. “Single signal hypersonic. ETA is two minutes.”

Aida looked over at Koss. There was only one possible explanation. The Etterans weren’t bothering to target the Admiral. They were going to annihilate the city wholesale.

“Get in the air, LT,” Aida said. “On our location, now.”

She tossed a bag to Koss, and told the little girl and the mother to cover their ears. Then she blew out the window with her bolt pistol.

“Pick out her three favorites,” Aida said to Carter’s niece.

“What’s happening?” she asked.

“Nothing we can’t handle,” Koss said. “Just do as we say, and everything will be fine.”

“Keep a time on it, LT,” Aida said to the ship. “Every ten. I want us out at forty.”

“Roger,” her top lieutenant said. “One minute forty-seven seconds now.”

Carter’s niece put the dolls in the bag and handed the bag back to Koss, who picked up the girl.

“Aida?” Koss said.

She helped Koss secure his helmet.

“Mommy will be right behind you,” Aida said, seeing the trepidation in the girl’s eyes as they approached the three-story drop to the street below.

“One thirty,” the top lieutenant said.

Aida could see the carrier approaching above. Koss paused at the edge. She couldn’t see his eyes.

“The second you get there, set your suit to shadow mine and drop it out the back ramp,” Aida ordered Koss. “I’ll catch it, suit her up, and follow.”

Koss nodded and lifted off. The girl didn’t cry out, but Aida could see Helen gasp as she clutched Koss for dear life.

“One twenty.”

Aida watched at the edge of the window, putting on her helmet and securing it. Koss climbed as fast as he could, but with the girl, it looked slow. Aida had thought it might be close.

“One ten.”

That meant thirty seconds, Aida thought, shaking her head. The added weight from the girl was too much. Aida looked over at Admiral Carter’s niece. Even through the helmet, it was as though the young mother could sense the calculation Aida was making, whether she should leave her.

“Please,” the woman said. “My little girl.”

“Twenty seconds, Captain!” the top lieutenant said.

“Suit’s out,” Koss said, just then tossing his drone suit from the ship’s back ramp above.

It was already over, though. Even if Aida managed to catch Koss’s gear, there was no way she could get it on the mother and guide them both to the ship on time. It was already too late for her as well in that crosswind.

“Burn hard, Rangers,” Aida said. “That’s an order.”

There was a half second of disbelief in their response.

“Go moon, Captain,” the top lieutenant said.

“Moon Rangers, go moon,” she heard Koss’s voice. Then two more on the crew. “Go moon.”

“Get out of here!” Aida shouted.

Then the carrier’s engine cracked, blowing out the glass windows through half the neighborhood.

After Aida regained her balance from the ship’s recoil, she turned around to see Carter’s niece shaking, hunched down with her eyes closed, bleeding in several places from the flying glass. Aida took stock of the neighborhood. She had maybe thirty seconds. The basement of the building was their best bet, and the window was the fastest way down. Her suit couldn’t carry two, but it could break their fall.

“Let’s go,” she said, gesturing to the woman. “Last chance.”

Carter’s niece perked up.

Aida opened her arms, and the woman ran to her and grasped her about the neck, jumping into her arms like a child. Then Aida jumped. They fell at maybe half speed, and it took nearly all three floors for Aida to right herself so they’d land on their feet, and still they landed in a heap. By Aida’s mental clock, they had twenty seconds to get to cover. She’d seen a side door, a service entrance that had to lead down.

Aida leapt up and took a few steps toward it, only to realize that Carter’s niece hadn’t gotten up, she was writhing on the ground behind her, clutching her ankle. Aida told herself she would go back for the woman as soon as she got the door open. Aida rushed over, only to find the door locked. She pulled a charge from her belt. Her hands were shaking. She set the charge, ran back a few steps, and blew it. The clock in her head was at ten.

Above her, a blinding flash turned the sky to starlight. She looked at Carter’s niece, seated helplessly on the sidewalk. It had come too early. Her last thought as she broke for the stairwell was that she’d made the right call. Any longer and they’d never have gotten away. She thought about her mother, her father, and the hall of honors, her name among the honored dead and the life of the girl, Helen. She leapt down into the dim stairwell and registered an unfathomable force coming down on her as the universe went from dull gray to blackness.

ONE DAY BEFORE THE BLAST:

They’d been rotated off for a cycle, following a ten-week tour hopping between moons defending the supply lines for Richfield. The stalemate slogged on. It seemed so for everyone but the combatants themselves, who, when the metal ran out, were thrust into the void to keep lines as they had been for nearly as long as Aida had been old enough to learn about the war. At ten, she became acutely aware when the brother of her babysitter came home to Carhall City in a box. What had her life been before that, a fantasy? That had been a product of the artifice her parents had constructed around her young life. It wasn’t that she and Omar were unaware of the war, but it was a distant thing, an adult thing, something that couldn’t touch her for ages—that was the gift they’d given her. After she was commissioned, she asked her mother why so much had been hidden from them.

“Before children know the way the worlds are,” her mother told her, “they deserve to have a memory of the way the worlds can be. Innocence is sacred.”

Innocent was also a way to describe the people out in these indies and much of the Letters. There was a tenuous tolerance for the Trasp out here at Alpha-Origgi, where Aida’s unit, the 76th Lunar Combat Specialists—better known as Moon Rangers—were patrolling. They scanned settlements like Alpha-Origgi for suspicious vessels, and, when things were slow, sometimes they took foot patrols in markets and gathering places to see the faces of the people, taking stock as they passed by. Rarely, it brought out something organized, a strike of angry citizens, furious that their supposed independent system would allow Aida’s people to land and walk about freely. More often, when there was an incident, it was just an angry friend or family member of somebody killed in one raid or another, for which, in their minds, the Trasp nearly always bore responsibility.

The people of Alpha-Origgi were not fighters. They were merchants. The marketplace she and Koss were strolling through was full, buzzing with foot traffic, and mostly, the people all but ignored them. The worst they’d gotten all day was a nasty look from a bartender across a busy causeway, and Aida wasn’t even certain it was directed at them. That was a good day.

“Bacca told me there was a stand at the farside fruit market that has rock melons,” Koss said. “I haven’t had a proper rock melon in ages, which means I haven’t had a proper breakfast in ages, Cap.”

Aida asked him to lead the way. Technically, they were on a patrol. That didn’t mean they couldn’t pick up a rock melon, though, maybe a bag of oranges. One of the grunts had even come back with pink apples. Aida wasn’t one to pull rank to get a taste of one, but it had crossed her mind.

Along the way, they passed through a corridor of carts that had a different character about them. They seemed less commercial and more decorative to Aida’s sensibilities. There were tall feathers, streamers, and garlands extending overhead. And there were innumerable figures and small statues on the shelves of these carts and spread out on blankets along the floor. Most looked like cheap printed polymer figurines.

“Can you imagine these people pray to these things?” Koss said.

“Oh,” Aida said, suddenly realizing what this section of the market was. She’d heard of places like this in the Alphas, but didn’t realize Alpha-Origgi was so replete with believers.

“I don’t know,” Koss said. “I think it should be illegal to take advantage of people like that?”

“Like what?” Aida said.

“Selling people these idols, as though there were anything to any of this nonsense. Taking advantage of naïve people’s superstitions like that. It makes me sick.”

She looked around the market at the merchants. She didn’t know why, but she got a knot up in her gut for what Koss had just said. It didn’t sit right.

“Look over at that woman, Koss,” she said, gesturing toward an old woman standing beside one of the carts filled with icons. “Does she look like someone getting wealthy preying on the unwitting masses to you?”

Koss shrugged.

“I bet she hardly makes enough to eat.”

“Somebody is,” he said, gesturing to the vast marketplace.

Aida began to walk toward the woman’s stand, if for no other reason than to piss off Koss, or at least make him squirm, force him to look that old woman in the eye.

The old woman took a deep breath as Aida neared—not an uncommon reaction for common folk when approached by a Trasp Moon Ranger. None of the stories these people told about Aida’s people were flattering.

“Greetings,” Aida said, placing her hands together and offering a slight bow, which was the proper greeting here on Alpha-Origgi, as she understood it.

“Greetings, sister,” the woman said, returning the gesture but not without trepidation. “How can I help you?”

“I’m merely curious,” Aida said. “We’re unfamiliar with your ways. You see our uniforms.”

“Of course. You come to learn or to mock, it matters not as long as it is in peace.”

“If he mocks you, he’ll clean the mess for a week,” Aida said, gesturing toward Koss. “We’ll be respectful. I’d just like to look, and to ask questions if that’s okay.”

The woman pointed toward the figurines on her cart. She didn’t seem too eager to interact at first. But as Aida and Koss engaged in conversation about the figurines, mostly wondering about their meanings and identities, the woman began to hover and listen.

“That shelf there,” she said, “those are Christian saints. You can eye the K-code to learn.”

“Where?” Aida said.

“On the base,” the woman said. “You may lift them.”

“Oh!” Aida said, turning over one of the figurines to reveal the hidden K-code.

“There is a saint that will hear your prayer for all your troubles.”

Aida could feel Koss biting his tongue.

“It is not so for you, you think, eh?” the woman said to Koss. “I have heard there are no religious Trasp.”

“I wouldn’t say none,” Aida said. “But it is uncommon.”

“We don’t have gods,” Koss said, genuinely making an attempt at respectful conversation.

“We all have a god, whether we know it or not,” the woman said. “If you think you do not, you merely don’t understand who your god is.”

“So you say,” Koss said, shrugging.

“What are those?” Aida said, gesturing to a panel on the cart where several rows of metal plates hung.

“Tressian,” the woman said. “Do you know of their holy warriors? They believe in one god and choose the conduit from many of the holy traditions of Earth and Charris. They are guides to the spiritual realm.”

“They’re beautiful,” Aida said, admiring the pressed metal imagery, scanning the rows with her eyes. “Is there a K-code for these?”

The woman shook her head. “They’re holographic,” she said, pulling one down and placing it flat on the cart’s front shelf. The plate projected a holographic image above it and began to play a basic introduction to the figure. The first one was for a burly European god named Odin.

“Oh, Omar would love one of these,” Aida said. “Do you have any for any sort of trickster gods or maybe one for wisdom. I’d like to get one as a gift for my brother.”

The woman shook her head. “I’m sorry. You don’t understand. You should not choose for another. You should only choose for yourself.”

“Cap?” Koss said, gesturing toward the fruit market.

“You’ll wait, Lieutenant. Show some courtesy.”

He shook his head, while Aida continued to look over the metal plates, talking with the old woman about each one.

“This one might suit you, dear,” the old woman said after sifting through several rows. “This is Leda.”

A hologram of a beautiful young woman and a swan appeared on the front shelf as she placed it down. Aida listened as the prayer card explained that Leda, mother of Helen of Troy, wept for the innocence of her children, as she knew the pain of having hers stolen from her.

“I love it,” Aida said.

“I can show you how to wear it,” the woman said, “the way the Tressian warriors do.”

“Sure,” Aida said.

“Cap?” Koss said.

She shot him a look.

The old woman gestured for Aida to follow her behind the cart. Koss put his hand on the woman’s shoulder to hold her back.

“It goes under the shirt, young man,” she said, gesturing toward the curtain behind the cart. “For her modesty.”

“This is against regulations, Captain,” Koss said.

“Am I what you fear?” the old woman said to Koss.

“Relax, Koss,” Aida said. “Take a deep breath and think of your rock melon.”

He shook his head as they disappeared behind the cart. Koss scanned the corridor anxiously while he waited for Captain Jemeis to re-emerge. This was how every bad patrol scenario started in training, with a team splitting up under dodgy circumstances.

“It’s just a market,” he reminded himself under his breath.

Finally, Aida returned from behind the cart, trailing the woman, and, from what he could see, there was no evidence of that plate on her person under her gear.

He came closer to the cart as Aida paid the woman far more than he would’ve believed she’d part with for such a trinket.

“Remember young man,” the old woman said. “If you do not choose your own god, someone else will choose it for you, and you may not like the outcome.”

He shook his head.

After they were out of earshot, he looked over at Aida.

“I was respectful to her face, Cap. But screw that old bat,” Koss said. “I can’t believe you gave her money.”

She smiled.

“I see,” he said. “You did it to piss me off, didn’t you?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Maybe I’m a little curious.”

“Yeah, a little curious, all right,” he said. “Bunch of nonsense.”

“Who’s she hurting?” Aida said. “Except your fragile ego.”

“These people are all so smug,” he said, looking around. “Choose your god or someone will choose it for you, son. Where does she get off, thinking she’s so in tune with the universe.”

“The way I see it, we all believe that there’s something special about us, something in all of us that makes us more than the sum of our cells. They just have a word for it. If that makes them crazy, then okay. Fine. I’m definitely a little crazy too.”

“I bet you catch a bolt right in that thing, Jemeis. Then we’ll talk.”

“If I’m still talking after I catch a bolt in the chest, you won’t have much to say then.”

“Smartass.”

“Dumbass,” she said. “Which way’s the fruit market?”

Four hours following that patrol, the 76th Moon Rangers were called to an emergency evac from the nearby independent colony of Kendry. They were to exfiltrate a retired admiral on the Trasp strategic counsel, who’d gone into hiding outside the Protectorate for unknown reasons. Intel suspected the Etterans had found him.

During the seventeen-hour transit, Aida fell asleep to the foreign but beautiful sound of the prayer for Leda’s children, spoken in the original Attic Greek. And, the following morning, the day of, before landing on Kendry, Aida shared a rock melon with her two lieutenants before dropping into the city of Maddutz. The 76th later returned with their target but without their commanding officer, Captain Aida Jemeis, who was listed on that day in the official record of the Trasp Protectorate as missing in action, presumed dead.